OK Ironman trivia freaks and stats nerds. Here’s one guaranteed to stump you.

Who was the first person to break three hours on the run in an Ironman? And when did he or she do it?

Many of you in possession of the current Ironman Hawaii media guide will raise your hands eagerly and shout out “Dave Scott! Two fifty three flat! Nineteen Eighty Four!”

And, if setting the record run could only count if the competitor finished in the top ten overall, you would be right. That is the proviso for collecting the prize money on the swim, bike and run primes to this day.

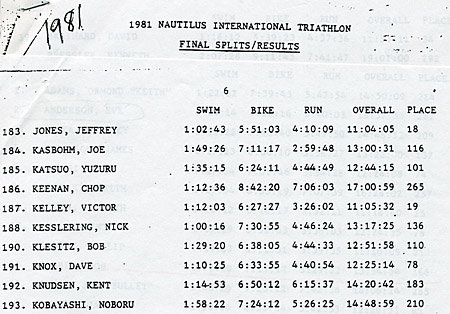

But if you look deeper in the 1981 Ironman Hawaii results, say 13 hours and 31 seconds, 116th place overall of 299 finishers, you will find a 19-year-old community college cross country runner from Bloomington, Minnesota, a fellow who never did another triathlon before or after, is listed in the results as finishing with a 2:59:48 marathon.

That split made Joseph Kasbohm the very first person to officially crack three hours for an Ironman marathon – quite a feat even to this day, 28 years later. “A lot of really good runners over the years took a shot at that mark and fell short,” said 1981 Ironman Hawaii overall winner John Howard, an Olympic cyclist whose run split that day was 3:23:48. “After a 2.4 mile swim and a 112-mile bike in the heat of Hawaii, it’s a really tough thing to do.”

In February 1981, the once cultish endurance test called Ironman Hawaii that began three years prior with an eclectic bunch of 15 hardy souls had grown to an event that attracted two-time Olympic cyclist John Howard and future triathlon Hall of Famers like Scott Tinley and Scott Molina. Now too big for the highways of Oahu, race director Valerie Silk moved the event to Kona’s highways, which had for 300 starry-eyed souls looking for the ultimate aerobic challenge.

A few days before that race, a skinny 19-year-old kid with a scruffy hint of a beard was in a crowded elevator at one of the Kona hotels with a bunch of Ironman aficionados speculating on the race. “One of the guys said ‘Dave Scott is not here, but we know who’s going to win the swim,’” recalls the young Midwestern unknown. (The savants guessed Scott Tinley, but it was Thomas Boughey) “And then another guy said, ‘For sure John Howard would win the bike.’ Then one of the guys said ‘So who’s the best runner?’ And I said ‘That would be me.’ They turned around and said ‘Do we know you?’ I said ‘Not particularly.’ ‘So where are you from?’ ‘Illinois. But I just moved to Minnesota.’ Then they said ‘You don’t know what you’re talking about!’”

Aside from that casual encounter, pretty much everybody dismissed the naïve kid with the unshakeable confidence. After all, the new sport of triathlon, Ironman style, was not at all like the Tour de France with plenty of opportunities for sprinters and climbers and time trial specialists to nab stage wins. It wasn't about ‘winning’ the swim, the bike or the run. As a new sport, the intention was to find out who could best combine these three hallowed sporting disciplines on one day.

Why pure runners almost never conquered the Ironman run

The early days of the Ironman showed that an excellent pure marathon time didn’t translate into posting an impressive marathon time. Gordon Haller, who won the very first Iron Man Triathlon on Kona in 1978, had placed 10th at the 1977 Honolulu Marathon in 2:29, but the best he could do at that first Iron Man run was 3:30:00. John Dunbar, the former Navy SEAL who finished second that year, was a 2:36 marathoner but his run split for his second place finish was 4:03. In his first three tries at Ironman Hawaii, Dave Scott ran 3:30:33 while winning the 1980 event, 3:21:02 while placing second in February 1982, 3:07:15 while wining the October 1982 event, and 3:04:16 while winning the 1983 event. In his first try at Kona in 1981, triathlon legend Scott Molina overheated on the run and DNF’d. In his second try, he ran 3:31:15.

Several top runners took their best shot at Ironman with a goal of running the fastest split and failed miserably in the accumulated heat and humidity and 6 or 7 hour warm-up on the swim and bike in the lava fields. Curtis Alitz of the United States Military Academy, a low 28-minute 10k runner in NCAA competition, who also finished the Boston Marathon in 2:17 and who took second place at the US Triathlon National Championships in 1984 (running down Scott Tinley for second place at Bass Lake), hit the wall in his Kona debut and finished the run in 4:19. Mike Cook, a 2:19 marathoner who worked for a triathlon related sports company, thought he might set fastest run in the mid-1990s – but finished the Kona marathon in 4:30. Pioneer triathlon coach Lew Kidder remembers Dennis Kurtis, a man who had done multiple marathons under 2:20 who thought he could set a good marathon time in his Ironman debut. But when the day was done in February 1982, the best he could do was 3:16:55.

Still, despite lack of knowledge about training, nutrition and heat acclimatization, there were some other Ironman pioneers who came close enough to three hours in those early Ironman marathons to show that it was possible. In that first Big Island Ironman in 1981, James Butterfield finished 7th overall in 10:31:26 and posted a 3:05:08 marathon. In February 1982, Scott Tinley got his Ironman game together to win in 9:19:41 and ran 3:03:45.

While respectful of Kasbohm’s obscure effort, Tinley offers a little perspective on the barrier breaking. “Look, that was a very good run,” said Tinley. “But it wasn't an all-time feat. You have to remember 1981 was another time. Even the best of us sat up on the bike. In the next few years, the top guys were folded up over the bars and going flat out for 112 miles and we were really hurting when we started the run. This young guy did some long distance training and had a strong run. But what was his bike split? Seven hours. Relatively speaking, he was well rested when he started.”

The making of an obscure Ironman run record setter

Joseph Kasbohm was born August 3, 1961 to a family of 10 children. While growing up in Mundelein, Illinois, he loved to run. While attending Carmel Catholic High School, he played several sports but was devoted to track and cross country all four years. As he recalls, he was open to new challenges. “I remember I used to run long distance,” he said. “But I liked the track, too. One day, I jumped on the track with one of my friends at Carmel and said ‘I want to run with you.’ I pulled some muscle above my right knee, because I was using fast twitch muscles and I was used to using slow twitch muscles.” During high school, he says he “saw that triathlon thing on TV. Then I was a runner, and biked a lot and grew up swimming in lakes. I thought ‘I can do that.’”

While that idea simmered in his head, he graduated and enrolled at the College of Lake County, a nearby community college with a cross country team and got serious about running. “Back then, I did long runs, 15 to 20 miles, three times a week,” said Kasbohm of that 1980 season. He recalls his total weekly mileage was about 120 miles a week, not uncommon in the bloom of America’s running boom. For Kasbohm, the hard miles were more a reward in itself than the times or ribbons. “One cross country race I remember they called out 4:09 for the first mile,” he says. “But it was the first mile of a cross country course and you can’t be sure they measured it right.” He recalls running a high 16 minute or low 17 minute 5k, and a 34 or 35 minute 10k.

The next year, his family moved to Bloomington, Minnesota and he enrolled at Normandale Community College, which cut back on sports and had no running program, so he did several local road races. “I remember I saw Garry Bjorklund run Grandma’s Marathon there. And I liked Bill Rodgers and Frank Shorter, because they were really good at the marathon.” That year, he decided that he had to go do that Ironman event in Hawaii. “I thought I’d be damned if I would let my fitness go to waste,” he says. In order to pay for the trip, he says, “I did carpentry stuff building a studio for this Christian broadcasting network,” he said. With community college and work, he didn't have much time during the school year, so he ramped up his training in the summer of 1980. “I used to swim, but I spent less time in the water and more on the bike and the run.” He bought a 10-speed Fuji bike for about $370 and had a simple plan. Using his running fitness, he would set out for long rides on the weekends. “I’d ride until I got too tired to go any further, then ride back,” he says. Those rides lasted 4 or 5 hours. He also ramped up his already impressive long runs. “One day set out about noon and I ran to Wisconsin and back,” he said. “I got back about 5:30 and it was about 40 miles.’

A quiet, modest but intense young man, almost all his runs and rides were solo, fueled by a dream. Except for his 40-miler, most of the time he rarely ate and drank just water. When he came back, he often lost 8-10 pounds from his 152-pound frame. “Then I drank and ate like crazy,” he says.

Honor Thy Father

Before he could take off for Kona, he had one significant hurdle. “My dad is real religious, and I try to be good” said Kasbohm. “He was a deacon at the Nativity of Mary Church in Bloomington. In the Catholic Church, the priest is top, the deacon, who can be married, is second. I know in the Bible, it says to honor your father and your mother, so I wanted his blessing.” When he revealed his plan to his dad, there was some initial resistance. “At first he said ‘It's not a good idea.’ Then he told me ‘When I was a kid, I took a plane ride to Florida. It was a one time deal.’ Then he said ‘Well, OK. I’m not for this. But if you do it, I’m 100 percent behind you.’”

Soon after, he sent in his application and entry fee and got a call back from race director Valerie Silk telling him he was in.

Two weeks out from the February 14, 1981 race, Kasbohm wanted to make sure he was ready to run a good marathon at Kona. “I’d never raced a real marathon before, so I wanted to see how ready I was,” he said. He carefully measured out a roughly square 2-mile course on the streets of Bloomington near Normandale – and ran it 13 times. “I just went and ran and when I got done and went home, it was 2:30. I figured it took me about minute to come back home. So OK, I ran 2:29.”

His curiosity piqued by a journalist asking about his long ago Kona adventure, Kasbohm said he recently went out and measured the loop with a cyclometer and it measured 2.03 miles.

Not quite Muhammad Ali: But a quietly confident prediction

Coming out of that elevator in Kona, Kasbohm told two guys he was going for 2:30 on the run. “One of the guys said ‘You know what? Just go for 2:50.’ I said ‘Man you want to make it easy for me.’ Then the other guy said ‘Kid, just break three.’”

On the swim, Kasbohm was careful to shield his eyes from the glare of the sun on the water. That’s because he was taking medications for epilepsy, Dilantin and Phenobarbital, and bright glaring light can trigger an episode.

Perhaps because he was minimizing his sighting, he soon veered off to the right. “At the start of the swim, I split off toward the ocean, so this guy on a surfboard was saying ‘No! No! No!’ but I thought he was saying “Go! Go! Go!’ Pretty soon I saw two dolphins up in front of me, so I looked back and saw I was way off course. So I swam back, went around that big boat out there and came back to the pier.”

After his extracurricular wandering, Kasbohm exited the swim in 1:49:26.

Bent wheels, rainbow mirages, and a huge mid-race meal

Once he changed clothes and got ready to go, he had a surprise. “When I got to my bike, the pine wood bike racks with zip tires at the end was on the ground. Somebody has knocked over my bike and the wheel was bent. I called a race official over and said ‘Are you OK for me to ride on it like this?’ Hr looked at it and said ‘Well, OK, you can put it in 7th or 8th gear. That will be enough.’ I said ‘Shoot!’ On the other hand, I was happy. Now I could finish the race. The wheel kind of dragged on you, but then I got used to it.”

When he first got on his bike and looked down at the spokes and chain, Kasbohm was mystified by a rainbow-like aura around his bike in the morning sun. “When the sun hit my spokes, you could see different colors around it,” he recalls. “I asked another guy getting on his bike and asked him ‘Can you se rainbow colors on your wheels?’ He said ‘That’s from salt water. Don’t worry about it.’”

Somewhere around Kawaihae, where the highway runs closest to the ocean, Kasbohm remembers looking out to the Pacific and thinking he saw whales splashing. Starting the climb to Hawi, Kasbohm remembers seeing John Howard flying by headed back to Kona. “I had 18 miles to go to the turnaround and I thought ‘Wow, he is way ahead of me. But at least I will get to finish the race.’”

By the time Kasbohm hit the turnaround in Hawi, he faced the first of two weigh stations, designed to determine if a competitor was dangerously dehydrated. While savvier competitors like John Howard sweated off weight like wrestlers and boxers before the pre-race weigh in, and Dave Scott later went to the in-race weigh ins carrying two full water bottles behind his back, Kasbohm was unprepared. “I am 5-feet 11 and ¾ inches and weigh 152,” he recalls. “When I first got on the scale, I think I was 140. I thought there is no way I was going to risk getting kicked out because I lost too much weight, which was 10% of my body weight, or 15 pounds. I was going to make sure I weighed enough, so I sat down and ate tons of granola bars, bananas, oranges and slices of coconut and drank water and some kind of sports drink to get my weight back up.”

When he weighed in again, Kasbohm said the scale read more than his normal weight. “The man at the scales told me, ‘We need more people like you,’” he recalls.

On the way back to town, asked an aid station worker where he stood. “He told me ‘You’re 74th and you’ve got 47 miles to go.’” He says was going well enough to attract some followers. “By then my stomach didn’t feel so full and I was still strong. When I looked back I saw a whole line of guys were riding behind me. They were drafting. But I just kept cycling and passing people.”

On the road back, Kasbohm knocked off his bicycle pump when reaching for a water bottle. “The pump went straight down between the frame and the ground and so things got bent more.” Kasbohm said then a tire started going low. “My bike was goofed up and was making chik chik chik sounds. The last bunch of miles was tough. I felt frustrated and pooped.”

The run begins

By the time he got to the bike to run transition at the Kona Surf Hotel, it was almost precisely 5 PM and behind more than half the field. But there was a silver lining. The brutal heat at midday was lessening, and Kasbohm would be finishing in the merciful relative cool of the Kona night.

“By then I didn’t feel so full and I thought all the food I ate would get me through the run,” he said. “It had been two weeks since that training run and I had rested up OK, so I was feeling pretty good. Running up that hill out of the hotel, my legs felt heavy, a little stale. I think there was a little bit of acid still in my thighs. But after 5-6 miles, I started to feel good. I passed a lot of people and people kept clapping but I didn’t think anything about it.”

In 1981, the run went up the hill from the Kona Surf, then turned left immediately on Alii Drive. The detour to The Pit would come a few years later. After a 6-mile stretch on Alii Drive, the run course turned right on Hualailai, left on Kuakini, and continued north out to the Old Airport, doubled back then left and east past the industrial section to the Queen K . Unlike a few years later when the run went straight up the Queen K for a mile past the airport, and the current course where the run turns for a long out and back in the Natural Energy Lab, the 1981 course turned in at the airport road and took the runners through the entire airport access loop. The significance of this course configuration was that the last weigh station was basically at the furthest point of the run. Anyone who made it there would have done the distance.

“When I got to the turnaround leading into the airport, I asked this guy directing the runners to make the turn ‘What time is it?’ When he told me the time of day, (7:04PM) I was pretty sure it was just past the 16-mile mark and I was about 2:04 into the run. I told him ‘Thanks a lot’ I had to think about it, but I figured I was down to about 56 minutes coming back to break three hours.”

In high gear down the home stretch

Climbing our of the final steep incline exiting the airport loop, he saw exhausted runners just coming in. “I saw runners walking and puking and I was glad I was nearing the end,” said Kasbohm, recalling his drive in the twilight to make his goal run time. “I figured this was the last time I have to really put it into gear.”

Going down the steep hill at Palani, Kasbohm was in form and feeling no pain. “I didn’t quite understand why, but people in town were leaning out of window and standing in the streets clapping. When I turned on the final street along the ocean, I thought ‘Cool!’ I was looking for something like a cross country chute or something like a finish line I was used to. But all there was was a rope above the course and a little banner in the air right near the big tree at the pier.”

With no watch and just a couple of reports, Kasbohm didn’t know if he had made it or not. “I thought I was just under, or right at, three hours. I didn’t know it was that close.”

On the official results sheet, which wasn’t available for a while, Kasbohm’s run was listed as 2:59:48.

Some friends from Montana, simply glad to see he had finished, saw Kasbohm and told him “Way to go Joe!” Kasbohm remembers Valerie Silk asked him “How do you feel?” “I told her ‘Pretty good. I could do it tomorrow,’” recalls Kasbohm. “But I got so sunburned, when I slept, my skin stuck to the sheets. I looked like a lobster and you could see streaks where my butt was. So I knew I couldn’t do it again.”

A quiet anti-climax

Kasbohm remembers talking to John Howard after the race. “I got this idea to get the swim and run and bike leaders to talk about how they did it,” said Kasbohm. “I said ‘Hey do you know anything about starting a magazine? Because, you know, if we take the guy who wins the swim, you do the bike, and I talk about the run thing. But he said look me up later. I was an English major and thought this may be a good idea to do some writing if this magazine ever came out. But I just laughed because I had this idea and didn’t do anything about it.”

Afterwards, Kasbohm liked Hawaii so much he wanted to stay. “I asked this restaurant that looked over the ocean if they had any jobs for a busboy, but they said they were full up,” he recalls. He was ready to keep looking, until he called his dad. “I said ‘Dad, I missed a few flights.’ He said ‘What!’ I said ‘I kinda like this place.’ He said ‘you get on that next flight!’”

When he was getting on the plane, he fell into a conversation with a strong looking man in a mustache who had finished just over 10 hours. “We were just talking about the race and he asked me how I did. I told him I got 2:59 something on the run.’ He just looked at me with a funny look. I said ‘Wait til the results come in.’”

A star crossed future

Sometime before he left Kona, Kasbohm recalls that Valerie Silk said “You’re coming back next year aren’t you?” “I told her ‘I’m in college.’ It was pretty expensive, so I made a promise I wouldn’t come back until I graduated.”

But as fate would have it, Kasbohm never graduated from college and never did another triathlon. He quit Normandale and enrolled at St. Cloud State, which had both cross country and baseball teams. “I ran at St. Cloud but I had to redshirt for a year. I ran OK, but my doctor changed offices and I could not run until they had my official medical records, so I ran a bunch of open races. I also tried out for baseball, but the coach said I was too old. I was 23.”

Ever the dreamer, he went three times to an open tryout for the Minnesota Twins minor league system held at nearby Metropolitan Stadium. “The first two tryouts, I didn’t do too good. The third one I tried out as a pitcher and they said I could come back and pitch a scrimmage game. But just then, some guy ran up late and threw BBs – all strikes – and they said they didn’t need me”

While at St. Cloud, he studied Physical Education with a minor in English. “My favorite author was Hemingway,” he said. “I like his style. He was simple and concise.”

He quit college his senior year. “I needed to work, he said. “At first I moved furniture. My second job I was a busboy at Denny’s. Then I worked as a janitor at the 89th Street Racquetball Club. They call it Life Time Fitness now.”

At age 29, he suffered a stroke. “It set me back some time,” he says. “For three months I couldn’t do anything. There was a lack of feeling on my right side and it was hard to talk and walk. When I could work, I lived with my sister and got a job at a Subway sandwich shop back in Mundelein Illinois. Then I got a job at the Center Lights Health Club near the Condell Medical Center. By then I had done speech therapy and was speaking more.”

Finally, he moved back with his parents in Bloomington and got a job at Cubs Foods in Baker Square stocking shelves.

By 2002, he was feeling good enough to train and race the Twin Cities 10-mile run with his brother. They finished in 1:30:11.

In the sad age of cheaters and fakers, why the author believes Kasbohm’s mark is for real

When I first started to track down the first man to break the 3 hour barrier in an Ironman run, I was warned to check it out thoroughly to make sure this wasn't another Rosie Ruiz. Everyone who had been there, from John Howard (9:38:29) to Scott Tinley (10:12:47) to Bob Babbitt (13:54:54) to Dan Empfield (11:22:54) agreed that regulation and course supervision was pretty casual in 1981. But given the major turnaround point and final weigh station was inside the Keahole Airport loop road, it seems there was no convenient place to cut the run course. Most of all, says Howard, “Back in those days, there was camaraderie, a kind of a sense of honor that everyone had about simply finishing the Ironman.” Ultimately, all we have to trust the official record.

By the time I finished this, I had not succeeded in contacting his high school or college cross country coaches. But in all my conversations with Joseph Kasbohm, I found him to be completely unguarded, never calculating, and simply happy to recall, in his often halting speech that gives evidence of the massive stroke he suffered, one of the happiest times in his star crossed life.

Finally, consider this. Rosie Ruiz hopped out of a subway and stole the ovation from thousands of fans that should have been reserved for the true Boston Marathon winner, Jacqueline Gareau. The same thing happened to Frank Shorter at Munich in 1972 when an imposter hopped onto the course and soaked in the cheers of a confused crowd in Olympic Stadium. Joseph Kasbohm crossed the line and nobody knew what he had done. Aside from some pals from Montana and race director Valerie Silk who simply congratulated him for his finish, he only mentioned his pride in his run time to a few fellow competitors he shared war stories with after the race. When he got home, he told his dad about his race and went back to school and back to work.

It was his fate to pretty much fall off the radar of the triathlon and running worlds, especially after his stroke. Given all the great pure runners who tried and failed to make a splash at the Ironman after the 7 to 8 hours in the sun wind and heat, it is simply fitting to recognize a Kasbohm’s remarkable first.

But there's another wrinkle to this tale.

Upon checking the tattered Xeroxed copy of the 1981 Ironman results, the splits listed for Joseph Kasbohm's 13:00:31 finish add up to 12:00:31. A member of the 1981 Ironman timing team who handled the swim splits only and not the final compilation offered the following probabilities. First of all, the final finish time is most likely accurate. Second, he verified all swim times. Finally, since the sum of the swim, bike and run splits are precisely one hour off, he says the most likely probabilities are that either the bike was 8:11:17 not 7:11:17, or the run was 3:59:48, not 2:59:48. "I'd say it is 50-50 where the mistake lies," said Dr. Fred Sayre, a Kailua-Kona dentist who was in charge of Ironman timing from February 1982 to 1989.

The 1981 program lists Lee Howard as the marathon and overall chief timer. As soon as we can reach him, the answer to this mystery will be included in this story and on the Slowtwitch forum.