Cadet Nicholas Dason had the world on a string. In high school in Terra Haute, Indiana, he excelled in swimming, cross country and track. A top student, he was student council president and a born leader with an inclination to go into politics. With his record, doors to several top colleges were wide open. But with both parents on teachers’ salaries and a brother and a sister also slated for college, the United States Military Academy, with its full scholarship and its storied tradition as a breeding ground of leaders, won out.

In his plebe year, Dason walked on the Division I swim team. With top performances such as a 16:10 for the 1650 freestyle, 4:10 for the 400 IM and 1:55 for the 200 butterfly, he was slated to serve as senior captain. Perhaps the only blot on his all around admirable record was an incident at a party at the Army-Navy game his sophomore year in which he was cited by a fellow cadet for underage drinking. Underage drinking is considered a less than major offense under the strict West Point Honor Code. The Academy has myriad rules and regulations, which start with making your bed properly, what uniform you must wear at what times, and proper civilian attire. If a cadet is caught for such a minor incident, the punishment is a veritable slap on the wrist – 5-10 hours walking the yard. Dason’s violation was a middle level rules and regulations transgression, which could be atoned for by some 50-100 hours spent walking the yard and other restrictions.

His world turned upside down

The next year, Dason again joined the corps of cadets cheering at the Army-Navy game. This time, he was of legal age to drink at the post-game party. But several cadets at the same party were not. Unlike fellow cadets who had turned him in the year before, Dason failed to report the underage drinking.

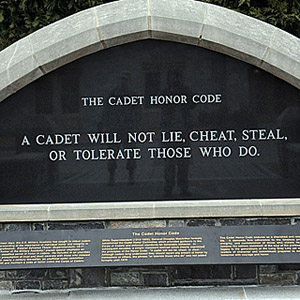

This was a more than a mistake. Under the West Point Honor Code, “A cadet will not lie, cheat, steal or tolerate those who do.” When a cadet commits or observes any rules and regulations violation, he or she is obligated to turn in the offender. When confronted, Dason immediately admitted his omission.

If a cadet breaks the rules and then lies about it, that puts the cadet into an inner circle of hell with regard to Academy principles. When a cadet lies or cheats or steals, fellow cadets see the violator differently. Often, such an honor code violator will have to repeat the year, or is simply kicked out. Always, they are put into an honor mentorship program to rehabilitate.

Nonetheless, Dason’s toleration was a repeat rules and regulations offense, and Dason was booted out of the Academy. Suddenly, shockingly, his world was turned upside down. As an upperclassman, Dason owed a military commitment, so he enlisted as a private first class, finished basic training, and was quickly deployed to Iraq.

Looking back on his actions, Dason now says “You can fight and die for your country at 18, but you cannot drink a beer. That does not make sense to me. But, given our commitment to the honor code, that argument doesn’t apply.”

Dason was distraught. “Imagine everything you had planned on and gone for all your life suddenly ripped out from under you,” he recalls. “On top of that, it was a terrible feeling having to tell my parents and family. When people I knew asked me to explain what happened, they all thought it was ludicrous. People outside the military and outside West Point thought it was crazy.”

Certainly, no student at any civilian college or university would likely have been cashiered for what Dason did. In the wider culture, the one that loves the bad boy protagonists of movies like Animal House, Road Trip, Risky Business, or Fast Times at Ridgmont High– Dason’s actions would be celebrated.

It is ingrained in the American character to love a rebel. After all, without a stubborn refusal to bend to authoritarian force, we would still be a British Colony, Texas would still be the property of Mexico and who knows what might have happened in World War II. Even in famed novels set in the military like Mutiny on the Bounty, our instinct is to side with mutineers and the anti-heroes who fight rigid bureaucratic rules that stomp on human values. In Catch-22, surreal military logic is the villain, and the heroes are the freewheeling wheeler dealers like Milo and humble humans like Yossarian who find military logic an inhuman oxymoron.

In Band of Brothers, a television mini-series beloved by soldiers about American fighting men in World War II, we see that the fundamental, primary loyalty of the soldier is to the flesh and blood men next to them under fire. More abstract notions like patriotism and love of country and flag are somewhere down the list. So while many Americans would admire the whistle blower who calls out corporate malfeasance which hurts people for profit, most would think anyone who turns in teens for drinking is a snitch.

But the West Point Honor Code sees a higher purpose in demanding of its cadets absolute truth and integrity in the smallest matters. They assume cadets will become military leaders in battle, and will be making life or death decisions depending on split second reactions under fire. If someone is thinking they are protecting a fellow soldier and provides less than the absolute truth at the instant he or she is asked, the lives of the entire unit are at risk. Furthermore, cadets study failures of integrity like My Lai and Abu Ghraib so that they can face critical situations with integrity drilled into their DNA.

“I made the mistake,” says Dason. “I was clearly wrong. I never argued that. And so I said to myself ‘You can either complain about it and be miserable, or you can suck it up and make the most of it.’”

Right around that time, he saw what thousands of people faced in the destruction of Hurricane Katrina and took a lesson from it. “I saw that people’s lives are ripped out from underneath them all the time, yet they rise up from the ashes. I decided to take a shitty time and learn from it. People who only know me on the surface say I haven’t changed much. But if they truly knew me, they'd see this incident had a huge effect on my life and that now I understand and appreciate things very seriously.”

Welcome to the suck

Dason was assigned to Ramadi, west of Baghdad. “When General Petraeus spoke to Congress with his big Power Point presentation about the surge, statistics showed that Ramadi was at the peak of violence in 2006,” said Dason, who was right in the thick of it during his tour of duty starting in January ’06. “I was in the Scout Platoon, 1st Battalion 506th Infantry Regiment, 4th Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault). Our job essentially was to patrol the city and neutralize the terrorist threat. My team was shot at quite a bit. One of my roommates stepped on an IED (Improvised Explosive Device) and lost a leg and a few fingers. We also lost a man from our platoon who was killed by sniper fire. If I sit here and tell you I wasn’t scared, that would be a lie. But the way to handle it is not to worry ‘Oh my gosh, will I be killed or not?’ If you’re worrying about it, you’re not doing your job. You’re not covering your sector.”

Dason found his background in swimming and running and overall fitness made a big difference. “Being one of the smallest and newest guys guy in the platoon, I carried the heaviest weight,” he said. “I’m 5-9 and weigh 160 pounds, and when I had all my mission essential gear on I totaled 300 pounds.” Dason found the endurance sports background -- and his insistence on working out whenever he could in Iraq -- made an even bigger difference on patrols.

“In Ramadi, I conducted operations on roof tops with temperatures north of 140 degrees,” he said. “You need to sit there and focus for hours. You need endurance and perseverance to push through and continue giving your utmost level of attention. If I weren’t as fit, I might get lazy, take some time off, and people would die.”

The life or death link between sports and military

Dason explains how training for sports relates. “A lot of times triathletes train by themselves,” said Dason. “You might tell yourself you cannot do that last set, that you can coast in without a full effort and nobody will know the difference. But if you have the integrity to always do the right thing; it will make you a better competitor. That same habit will translate into the discipline to do the right thing in battle.”

Dason feels that discipline was directly responsible for saving the lives of fellow soldiers one day at a checkpoint. “We had intel come down there was supposed to be a suicide attack,” recalled Dason. “This guy drive up to a checkpoint and prior to pulling up to the security guards, I observed the guy get out of the vehicle and begin to wave with both arms. We’d been taught that the wave was a typical tactic to get fellow insurgents to begin video taping so the bombing could be used for propaganda. The security guards told the man not o proceed through the checkpoint. However, without being prompted he began to drive through the checkpoint and that is when I signaled my fellow soldiers to shoot. They took out the man and the vehicle, which erupted with some secondary explosions, indicating that the were in fact explosives in the vehicle. That decision saved people’s lives.”

Dason recalled the moment with quiet clarity. “If I hadn’t been paying attention o might not have seen him wave his arms. If I had been tired, I might not have seen those details that added up to the conclusion that this guy’s bad and he was going to blow up a car bomb on our men. To just sit there for hours in that incredible heat and stay focused, that is one way that endurance training helps so much.”

Welcome back

During his tour in Iraq, Dason decided to apply for reinstatement to West Point. “A lot of people could not believe I wanted to go back and serve more time when I graduated, since my commitment would be extended,” said Dason. “But ultimately, I wanted to go back to West Point to be a leader and an officer. It’s what I like to do. It's what I’m good at.”

Dason’s love of country was also amplified. “Serving in Iraq made me appreciate all the smaller things that we enjoy in the United States,” he said. “The privilege of driving down the road and not having to worry about getting blown up. Being able to run without putting on full body armor. Not having to worry ‘Can I get food tomorrow? Can I get enough power to read at night?’ Many people live in a bubble and never see how tough it is in other parts of the world. I always believed everyone should serve our nation in some capacity or another. Only a few can be a part of the corps of cadets. But there is also the Peace Corps. Americorps.”

His baptism under fire didn’t some without come cost that all soldiers pay. “When I came back, I could watch movies and read books about other wars, but not Iraq. When I went to Disney World with my family, the fireworks show when the park closed really bothered me. As I got further away from the battlefield, that feeling eased off. Ultimately, nothing made me dysfunctional as a military officer. But I can tell you that post traumatic stress is very real, and it affects a lot of soldiers.”

Tri Times

When Dason re-entered West Point in January 2007, the swim team was midway through its season. He had not been able to find much if any pool time in Iraq. . Dason had done a few triathlons for fun, and he was eligible for at least one full season. Finally, he liked triathlon team adviser Colonel Pat Sullivan’s new, more rigorous training regimen and more ambitious goals.

Cadet Nicholas Vandam, a fellow member of the swim team with Dason, kept in touch all through the Iraq deployment, Vandam made the move to triathlon with Dason, along with several other cadets with major sports experience. Vandam says that Dason was a natural born leader. “He is so good, so enthusiastic, so charismatic, he was the kind of guy you’d follow anywhere,” said Vandam. And so Dason was chosen team captain for the 2007-2008 academic year.

Dason says “Triathlon is a club sport, but the recent popularity of the USA Triathlon Collegiate Nationals has given triathlon more prestige. I think I brought an NCAA attitude to our team. I wasn’t shy about telling people what I think about the work ethic, and motivational level required to go for a national title. The younger guys and girls saw me and other NCAA Division I athletes who came to triathlon give our all every day, and I think we influenced them. When we all started beating ourselves up in practice every day, it developed a camaraderie. You push yourself physically and emotionally in training and races and it becomes almost like a family. So when we finished classes and our second workout, we’d all go to dinner together for 45 minutes and have a good time.”

With his 10th place finish, Dason led the US Military Academy men’s triathlon team to third place at 2007 Collegiate Nationals at Tuscaloosa. Quickly adapting his swimming power to newfound skills in cycling and running, he improved his game for the 2008 Collegiate Nationals, crossing the line in 9th, 12 seconds ahead of the fast improving Vandam. However, a drafting call dropped him to second Army competitor, and 18th overall.

Helicopters and keeping the triathlon dream alive

Right now, Dason keeps in touch with the team, but as a West Point graduate, he’s up at 3:30 AM most mornings on a flight line at Fort Rucker in Alabama, learning to fly helicopters and preparing to serve in any area of conflict his country requires. In his off hours, he’s training for triathlon for the usual reasons: He wants to earn a spot in the Army’s World Class Athlete Program. “And it makes me sharper and stronger for those 12-14 hour days on duty.”

He is a little bashful about his old episode as a black sheep. “I guarantee you’ll get a lot of letters if you think it’s important to tell that part of the story,” he said. In case anyone misunderstands, we think Nick Dason, with the lessons he's learned and his recommitment to Army and the code of honor, is an example of the best tradition of the Long Gray Line.

Epilogue: Nicholas Vandam tells how Nicholas Dason taught him what being at West Point was really about.

I met Dason at the West Point Triathlon, and while we never had much time to hang out and get to know each other we instantly became friends and developed a connection through racing. My plebe year I was thinking seriously about leaving West Point. At the time Dason was in Iraq and I emailed him frequently and update him with what was happening. During this time of personal indecision, I talked to Dason and a couple other people about how I felt and what I was going through. He along with my parents and Bahram Akradi, (the CEO) of Life Time Fitness, a mentor and friend in my home town of Minneapolis, really convinced me to stay.

To be completely honest, before Dason came back to West Point I still was not sure what I was doing here. I did not really want anything to do with the military side of things, I knew I wanted to swim and do triathlons. I was recruited to swim here and I was sure I would serve my time in the Army. But I did not know what West Point was really about. So when Dason got back in January 2007, I joined the tri team the next month and we started to hang all the time. He told me what the Army was like and through hearing his stories and listening to him talk; I started to understand why I was here, the meaning of this place. I took his experiences and thought to myself ‘If he can go through so much and still come back here, I know this place had something special.’ Before, I was only concerned with myself and training -- not the Army side of things. Dason made me see that I was not here for any of that, I was here to serve the nation and be a leader in the Army. His story showed me that. He is one of those guys who just inspires you. So he continued to teach me what the Army was like, what a true leader is, and showed me how I should act, because I was screwed up. It’s hard to understand what West Point teaches you and why they do what they do. But when you meet a guy that has been in combat and seen all these things, it all comes together and you understand why you learn what you do here. He helped me put all these pieces together. His friendship has shown me how I should act as a leader.