Most of California is in a haze of ash. More than 800 fires are burning throughout the state. No part of the California is spared the atmospheric fallout, save the far south and perhaps some coastal communities.

It is an annual ritual for us, where I live, to flee our homes in search of clean air. There's always a fire during the Summer or Fall in California, and at some point or other, when the wind is right, or should I say wrong, the ashen air will find us. My road trips during this time of year are therefore impromptu, arising as a pursuit of blue sky. Three days ago the ash and haze set in here. I threw the camper on top; the bike on the back; and three of the dogs inside the truck and off I went, northbound.

I have a secret spot for times like this. It's just two-and-a-half hours by truck, and I'm in the High Sierras at 6500 feet in elevation, 9000 feet available if need be. Unfortunately, as I got ready to turn left off Highway 395, and climb to the place where I thought the air would suit me, I saw plumes of smoke in my path. My secret spot was the site of one of California's 800 fires—one of the bigger ones. In fact, this fire seemed to be the cause of the ash settling in on my home.

So further north I went, now having picked up as a passenger a Pacific Crest Trail thru-hiker. The PCT was closed in the area of my secret spot, and he had decided to skip 40 miles of the trail, rejoining it up the slope from Lone Pine, California.

The further I drove, the less sure I became that I would get out from this cloud. There was no end to the ash and smoke.

So I turned to my last resort. Turned right, to be precise, at the town of Big Pine, ascending the final climb on the final day of the Everest Challenge bicycle race. State Route 168 climbs from 3700 feet above sea level to 7300 feet, splitting the White and Inyo Mountain ranges at Westgard Pass. At the summit of the pass, riders, and Bristlecone Pine enthusiasts, and those seeking the cleanest air in California, make a left-hand to ascend White Mountain Road. A further 11 miles up the road turns to dirt. By this time, you're 10,000 feet above sea level.

The dogs, and I, slept here, awoke and exited the camper to.... smoke and ash. Even here we didn't find smoke-free air.

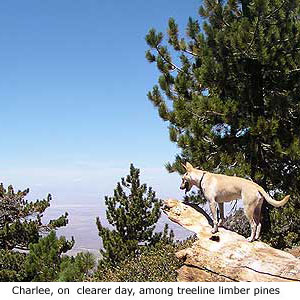

Nevertheless, we ran for an hour, very slowly, not because of fouled air. The dogs and I were approaching 11,000 feet in elevation, and while they were not bothered by the altitude I was. I could see the "top" of the ashen layer. I was within several hundred feet of blue sky. So, if I were atop Mt. Whitney, or Lyell, or Brewer, or any of the Sierran peaks above 13,000 feet, I'd be in good shape. At least in this part of California that was where things stood.

I drove back down to the Owens Valley and up to Bishop, California. I spoke to a gentleman who'd just driven down from Reno. He informed me that I would not find clear sky were I to reverse his route. It appears the ash from the Northern and Southern California fires had joined, and almost the entire state was enveloped in one grey cloud of ash. I turned the truck around and drove home.

I think clean air is a birthright. Nobody has the right to foul another's air, not with pollution, cigarettes, or with any other man-induced particulate. But this is different. These fires were all started through dry lightning: electrical storms that do not produce rain. This is not the first time it has happened, and it's not bad as bad goes. In August of 1910 the West suffered its worst-ever conflagration. To express what happened in Idaho's Bitterroot Range, I quote from Donald Culross Peattie:

"As the small fires increased to some 3000, a curtain of resinous smoke spread over the whole region. Lights burned by day in peoples' houses. Train conductors had to read the passengers' tickets by the light of their lanterns. The oppressive air was strangely quiet—sounds seemed to be swallowed up; birds staggered in their flight, and horses rolled their eyes, straining at their halters. Then, on the night of August 20, the superheated atmosphere over the whole area, rising, sucked in winds of hurricane force. Forest rangers were almost blown out of their saddles; acres of timber went down like kindling. And the small fires were whipped, in a matter of moments, into great ones."

Residents and forest rangers reported seeing a "star" falling afar off in the forest. The "stars," as Peattie explained, were "just the perimeter phenomena of as frightful a calamity as ever befell a forest. For as thousands of small fires were lashed by the winds into seething holocausts, an area hundreds of square miles in extent became so superheated that the resins in the virgin and mighty coniferous stands began to volatilize until great clouds of inflammable hydrocarbon gases were formed. And these, catching fire all at once, simply exploded in one screeching detonation after another. Tongues of flames shot into the sky for thousands of feet. Whole burning trees were uprooted and sent hurtling far ahead as gigantic brands. Flames tore through the crowns of the forest at 70 miles an hour. Settlers' cabins, railway trains, towns, were suddenly engulfed in seas of flame."

For the rest of this story, and many other stories, I suggest to you, "A Natural History of Western Trees," by Donald Culross Peattie, Houghton Mifflin, 1950. It is absolutely my favorite book. I refer to it for knowledge, and read it as a sort of amateur naturalist's devotional. It's been at my bedside, along with whatever lesser book I'm currently reading, for the last decade.

I could rant against the air around me, or absorb it as an exhale nature serves us from time to time. I'm very fortunate. This is the exception to the air I normally breathe. For much or most of the rest of world, it's not that way.