The Olympic Games in Ancient Greece were contested continuously for 1200 years. They first appear in 776 BC, but I doubt the concept of athletic competition was plucked from thin air. Only its organization on a grand scale was new.

Even so, the Olympics weren't the first. Footracing in Ireland was a part of the Tailteann Games, which dates back to at least 1600 BC. Long distance footrunning has long been a staple of some New World inhabitants.

But if you research the history of endurance sport what you find is documented footracing for thousands of years, then poof, gone, nada, reconstituted in England in the 1830s. In the literature there's a chasmic interregnum between the ancient and modern eras, as if the very notion of endurance competition vanished for 1300 years.

I have a hard time believing an inkling – a human idea – can just vanish. Maybe we don't know about footracing between ancient and modern eras because the time in between lacks documentation, not participation. The sportswriter is a recent construct. But not the sport. Primal-skill sport – who can chuck a spear or shoot an arrow the straightest, and who can run the fastest and farthest – is a social celebration of skills necessary for life.

But the line between the real thing – the need to explore, discover, conquer – and the proxy for it blurs. The only difference between the real and its proxy is the risk and the prize purse. If you're John Wesley Powell you might have an interest in white water competition (even with one arm blown off in the Battle of Shiloh). Just, for Powell, the competition was to be the first to navigate the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon (accomplished in 1870; Powell is pictured above).

Reading about Lewis and Clark, Jedediah Smith, and John Wesley Powell feels, tastes and smells something in the same genus as the sport I enjoy, along with the two greatest tales of survival in North American lore, that of Hugh Glass, finally brought to the film in a major way (The Revenant); and the very best, the one you've never heard of, him of the unfortunate name: Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.

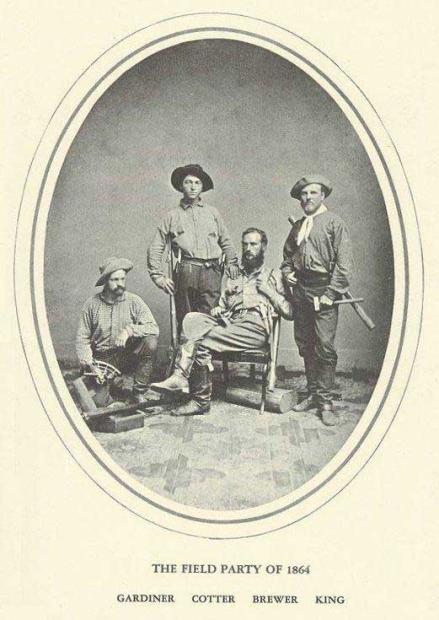

What I feel when a bike or pair of shoes takes me high and deep in the mountains is a small slice of William Brewer's day as he kept his journal, Up and Down California in 1860-1864, documenting his experience as part of the California Geological Survey. Just as Thomas Jefferson sent Lewis and Clark out to kick the tires of the land he just purchased, no one governing the new state of California was much acquainted with its resources, geography, ethnology, or natural history. So they sent these guys out.

The Sierran high points, Mounts Whitney, Brewer, Hoffmann and Cotter, are named after expedition members. Clarence King often peeled off during his science work to bag one of his many Sierra Nevada first ascents. Expedition members were the first to view Kings Canyon, now a National Park.

Brewer was the survey's botanist and he kept a crackerjack journal. These were scientists (Clarence King became the first director of the U.S. Geological Survey, Powell was its second director), but when you read Brewer's book, even more King's Mountaineering in California, these read much more like descriptions of extreme and endurance sports undertaken on the boss's dime.

While you and I rely on the precise correct formulae for on-board fuel, John Muir, “tied a crust of bread to [his] belt,” and was off for days or weeks exploring Yosemite and the High Sierra with nothing but a coat to warm him at night.

Jedediah Smith was a partner in a fur company. Like oil companies today, denuding the land of its resources diminishes your inventory. Smith decided to explore for previously undiscovered rivers to depopulate of beaver. He was the first white man to cross the southern traverse of North America East to West, and the first to cross West to East via the central traverse, over the Sierra Nevadas.

In one of his excursions Smith was mauled by a grizzly bear, his scalp and one ear ripped almost off. Smith had to coach a fellow traveler through the surgery as the novice sewed his face back on. Imagine. And then Smith wrote about it, and you can read it.

Jedediah Smith's two round trips to the West Coast, up to the Pacific Northwest, his success in business, was cut short when he was killed by Comanche Indians in yet another expedition – at the ripe old age of 32.

Strikingly, all these above (except Hugh Glass) kept clear and riveting journals. They're all widely available today. With respect to the many books written by contemporary runners, cyclists and triathletes, these journals are my multisport devotionals. One thing I appreciate about Mark Allen's book of last year, The Art of Competition, is that it offers no specific instruction. It's a celebration of sport that has more in common with Thoreau and Ansel Adams than anything any triathlete has written in the past.

Why do these accounts above from explorers and surveyors, who are not athletes per se, resonate and nourish my multisport life? Beats me. But they do.

[This is the 3rd of 5 blog entries on the subject: Letters to a Friend; No Skill for Living; Who is an Athlete? Subversive Tri; The Boundary of Sport]