It’s no secret that a lot of original equipment spec is getting pulled off tri bikes in favor of aftermarket changes. While motorcycles, automobiles, and even road race bikes are often ridden as spec’d by their makers, tri bikes are rarely ridden without at least one item changed out of three key components: crankset, saddle, and aerobars.

It’s likely such changes are made from time to time because a specific product catches the eye, or the imagination, of the consumer. At the same time, when a particular category of product is routinely pulled off a bike in favor of something else, a manufacturer is, or ought to be, pressed to consider whether their spec choices are appropriate.

Further, retailers ought to be concerned as well. It’s terribly inefficient to absorb unsalable parts into inventory. For example, how many 175mm 53x39 FSA Gossamer Mega Exo cranks are going to be sold aftermarket during the course of the season by a tri retailer? What do you do with all those OE saddles?

The tally of superfluous money spent doesn’t include service work changing those parts out, the cost of which is either absorbed by the retailer (a loss to him) or charged for by the retailer (a loss to you).

To what degree, then, is every new complete tri bike sold with two cranksets, two saddles, two aerobars, all of which are purchased by the end user, but only one of which per category can be ridden—the redundant crank, aerobar, saddle, sitting on a shelf, paid for, but unused and destined never to be used?

To that end, we’re running a poll on Slowtwitch right now and, while not all the votes are in, it’s obvious that triathletes are swapping out these three key elements routinely. In fact, among Slowtwitchers, it’s rare to find a rider who hasn’t swapped out at least one of them. As of this writing, well fewer than 10 percent of respondents are riding a bike without changing cranks, aerobars or saddle.

Why is this? Two big reasons. First, the cranks—and it’s the crank arm length here—is determinative of how the bike will fit, and what angles the body will form while riding. A rider’s hip angle, throughout the pedal strike, will change if a change is made in crank arm length. Changing the aerobars affects the same angle. Assuming changing the aerobars means a geometric alteration in the spatial relationship between the armrests and the saddle, the hip angle is again altered. So, your ability to generate power and leverage is dependent on both the right crank length and an aerobar that provides you your correct armrest elevation drop.

Even more important is the fact that all three of these components, but especially the aerobar and the saddle, are contact points. Every place you contact the bike is a place that must serve two goals: function and comfort. A brake caliper must function, but it doesn’t need to be comfortable. Likewise a bottom bracket. But a saddle has both a structural function and it must be comfortable.

Certainly, it’s unfair to expect that OE spec wll never change to accommodate a customer. But it’s up to the bike maker to spec parts that are less likely to change. For example, entry level road bikes never have tall gears. A look at SRAM’s newest gruppo, Apex, shows that SRAM anticipates this, by featuring a long cage rear derailleur. The decision to place a long cage on an entry level gruppo's derailleur speaks loud and clear that this will often be paired with something like a 50x34, 11-28 set of gears (that long cage will suck up all the chain required for a bike with gearing featuring 33 total teeth).

Since bike makers anticipate spec’ing their bikes to match the expected customer, is it too much to ask them to do the same for tri customers as they do for road customers? To that end, here are our recommendations for how to approach OE spec going forward.

Aerobars (geometry)

There is a fit mandate, and a comfort mandate. As regards fit, the most important thing for bike companies to understand is that aerobars ought to complement frame geometry. If you’re a company that makes a bike that’s a geometric middle-of-the-roader, then you have a little wiggle room here. Middlin’ geometries might be those that range from the only moderately long and low bikes, like Cervelo’s P1 and P2, to the only moderately narrow and tall bikes, like Trek’s new Speed Concept. On these bikes, placing an aerobar with a low profile armrest or a high profile bar is not going to take the bike out of the range of geometric acceptability.

But if you make a frame the geometry of which is more stridently toward one end of the spectrum or the other, beware of spec’ing a bar with the same sort of geometric trend as your frame. For example, a Profile Design T2 is a high profile bar, with armrests that sit 6cm above the centerline of the pursuit bar. Such a bar spec’d on a Scott Plasma or Cannondale Slice (and both these bikes have models spec’d with this bar) means the bike is going to sit outside the fat of the bell curve. Certainly, some riders with long legs relative to their torsos; or who ride shallow, with higher aerobars—perhaps because they’re physically disqualified from riding a typical tri position—might find this an ideal set up.

While these bikes so-spec’d will undoubtedly be perfect for certain riders, these bikes’ product managers are splitting a pair of 5s on the blackjack table. They’re not playing the odds. Theyr’e specing bikes for outliers. Better is a bike spec'd like the Scott Plasma LTD, pictured above: a taller frame matched with a lower profile aerobar.

Likewise, spec’ing a low profile bar, like a Visiontech clip-on, onto a Kuota Kueen K, or a Kestrel Airfoil Pro (especially in it’s largest sizes), or on a Cervelo P3 or P4, means these bikes are skewed toward a particularly aggressive rider. Better for Cervelo to spec a 3T Mistral (and better yet if it’s with 3T’s Ventus armrests).

Felt is on the edge of precisely this with its 2010 line-up. It’s newly designed Bayonet fork places aerobars lower than the old Bayonet. So, this low-profile fork, sitting on a moderately low-profile frame, is spec’d with a very low-profile Devox aeobar. The combination of these three geometric elements mean that Felts (especially the more upscale models with the Devox aerobars), are locked in, as spec’d, for aggressive riders who choose steep configs and a fair amount of armrest drop. Of course, one can change out these aerobars for bars with a higher profile armrest, but, the point is to fit the fat of the bell curve out the gate, with the OE spec, rather than fitting the fat of the curve only after substituting the aerobars.

Aerobars (comfort)

I’ll write about extensions separately, and in more detail, but, suffice it to say: Extensions on OE bikes are in bad need of a makeover.

There are two OE, and two aftermarket, extension shapes made today that represent the newer, better way extensions should be made. The aftermarket shapes are HED’s lazy-S bend, and Blackwell’s Wrist Relief. Indeed, Blackwell’s extensions are no longer made by Blackwell, however a call or email to John Cobb might net you a set of these.

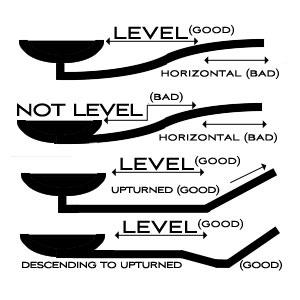

The two OE extensions I admire are those made by Felt and Bontrager. (Felt's F bend can be cut just upstream from the final bend, leaving the rider a simple, single-upturn, bend that many riders favor). Alas, Bontrager makes an extension that is perfectly sensible and comfortable for its higher end bar (pictured), but, resorts to an uncomfortable S-bend shape for some of its downspec bars. Note to Bontrager: Every extension has to be bent into something. Why not bend them all into this comfortable shape pictured here?

Saddles

There are three ways to go here, and, I’m ambivalent. My view: Just ship the bike without a saddle. If I was making bikes today, that’s what I’d do.

But I can appreciate that some bike makers are constrained to ship their bikes with saddles, and even really cheap, absolutely useless, clip-and-strap pedals in order to avoid getting hit with higher import tarifs, should U.S. Customs decide that the bikes brought in from Asia are not “complete.”

Fine. If this describes said company, then let’s be under no illusions about the saddle. It’s about as useful as the packing material that keeps the bike safe in its box. It’s to be thrown out. As an end user, just know this. Know that this saddle probably cost the manufacturer $4, maybe $6. The saddle is not to be ridden. You need to buy a new saddle commensurate with buying the bike. This, except if by freak luck you happen to find that the saddle is comfortable for you. Which you can determine before you take the bike out the door of your LBS, by placing the bike on a trainer and riding it. Just make sure you also ride your new bike with a Cobb V Flow, and a Fizik Arione Tri II, and a Profile Design TriStryke, and an ISM Adamo. If you still like your $4 OE saddle, fine. Otherwise, that saddle should go into the same “storage area” as the foam corrugated cardboard that kept the bike's front wheel from damaging the frame while all were in the shipping box.

The other option is for the bike company to spec an actual made-for-prime-time, tri saddle. Like a Cobb, or a Fizik, or a Selle Italia SLR T1. In this case, the bike maker made a good faith effort to solve your comfort problem, and, if the effort failed, the LBS is absorbing into his inventory a saddle he can turn around and sell aftermarket. Just know that your LBS could, and should, make an even (or close to even) swap if he pulls off a Fizik Arione Tri II spec’d OE for something else in its competitive set. Just know that your LBS is not going to give you any store credit for the $4 OE house brand OE saddle he pulled off your new tri bike nor should he have to.

Then there are the tweener saddles—saddles like the Specialized versions that go on Specialized Transition bikes. My own experience is that Specialized makes good helmets, and also very fine cycling shoes, and Specialized thinks its saddles are as good as its helmets and shoes. But, they’re not there yet—not in my opinion. And they’re especially not there yet on their Tri Tip tri saddles. But I have sympathy for a company whose “house brand” is more than just a product with the company logo, rather, the Specialized brand does have substantial value as a separate component maker.

While Felt has done a bang-up job on its Devox aerobar; while Bontrager has emerged as a leading aftermarket wheel company with a well deserved reputation; while Specialized deserves accolades for its products across a spectrum of categories; none of these companies has cracked the tri saddle market yet with a product that deserves to be considered among the elite.

Cranksets

There are several reasons to change cranks from the OE spec, but weight, stiffness, sex appeal, or shifting function, are rarely the reasons triathletes will cite.

Rather, the two reasons are gearing and crank arm length. Many triathletes find themselves overgeared if they live or race in a hilly region. And, being overgeared is a bad state of affairs in an atmosphere where power output during a race should be constant (not subject to spikes during ascents); and where cadences should also be constant, and, relatively high as bike riding goes.

The logical choice for overgeared bikes is a less overgeared crank. Enter compact cranks, aka 110mm bolt pattern cranks. This allows for small chainrings of 36 teeth, or as low as 34 teeth.

The other reason to change to a new crank is to change your crank arm length, and, it's always to shorter crank arms. This, as explained above, is to expand the hip angle at the pedal stroke’s top-dead-center. The rush is on to swap out 175mm cranks for 170s, and 170s for 165s.

Best, then, for the bikes to be so-spec’d from the manufacturer, right? Sure, but, this presupposes the bike maker has gotten the memo on crank length these days, and, since few have gotten the bolt pattern memo, why should we believe they’re getting any memos? Nevertheless, tri bikes should be coming, OE, with arm lengths 5mm shorter than would come on a road bike built in the same size. I’m 6’2” and I road ride with 175mm cranks, yet my tri bike is built with 170mm cranks.

Stems

Finally, stems need to be about 2cm or 2.5cm shorter than those spec'd on that same rider's road race bike. I ride a 12cm stem on my 60cm road bikes. I ride a 9cm or 10cm stem on my tri bike if I can get away with it (if the frame allows me to ride a stem that short) and 11cm if I'm riding a narrower bike and I need the cockpit length. Never will I ride a tri bike with a 12cm or longer stem—too much weight cantilevered in front of the steering axis.

Bike makers that sell their bikes with flatter stems (between -8° and -17°) as OE pitches, with stems appropriate in length to the size of the bike, are doing their customers a favor (both sets of customers: the store and the end-user).

One more thing, though. Can we agree that stems often need to be changed, even if to a size 1cm longer or shorter? Can we also agree that this stem, to be replaced by another, ought to be usable, by the retailer, during another future bike transaction? Can we agree that it's difficult for retailers who sell six bike brands to have entire stem runs from six different bike brands, along with the size and pitch runs from the aftermarket stem makers they feature in their stores?

So, bike makers, can you please stop putting your name and logo on the stems you spec OE? This just makes life for the LBS harder. And here's my final memo: customers probably don't want to put a Brand A-emblazoned stem on a Brand B bike. So, unless you really, truly, think you're in the stem business. If you employ an OE salesman to sell your stems to other bike manufacturers, then, yes, you're in the stem business. But if you don't, you're probably not.