In closing out this series I’ll tell you where I think we’ll be in 5 years, that is, what shoes we’ll have available to us at that time.

Now that I have thoroughly hammered the barefoot running movement, let me draw back a bit and place both this, and other, footwear movements in a perspective that I think might give us clues toward the future.

What we see in footwear right now is abject chaos, but, good chaos in my opinion. It’s like when the Soviet satellite countries were suddenly thrust out and left to their own devices. What do you do with freedom when democracy shows up and now you have to make decisions? Barefoot running freed the footwear industry, and now the industry has to make decisions. It can’t just fall back to making incremental changes.

Nike is – what? – up to $30 billion in annual sales now? New Balance is upwards of $2.5 billion, Asics is $1 billion? Brooks might be hovering around a half-billion in sales, but its growth overall and especially in performance running has been astounding over the past few years, with annual growth spurts of 30 to 35 percent, more or less, in successive years, year after year. Saucony is smaller yet but still has seen solid double-digit growth in tech running for consecutive years.

These companies represent the largest chunk a U.S. tech running market approaching $8 billion. Each of these companies has had its trajectory bent by natural running. Shoes like the high performance models from Newton, Brooks Pure Project, Nike Free, New Balance Minimus, Saucony Kinvara (just below), and tech running newcomers like Altra, ON Running and Skechers all, to one degree or another, show the influence of footwear that is lightweight, unstructured, flexible and, well, free. Nike has, since the mid 1980s, had this thread or strain running through its footwear line (e.g., the Sock Racer).

This isn’t going to go away. My argument with the barefoot running movement is not the shoe or the style, rather the narrative that this is a style of running for everyone, and that if you really want to explore the fullness of running you’ll do it our way and in our shoe style.

But I know barefoot runners who are happy as clams, whose feet are healthy, who don’t get injured, and who represent the best of running and multisport. A group of athletes – owners and managers – make their way from the UK to The Compound every year for bike fit workshops. It’s the folks from Ten Point just northwest of the M25 loop outside of London, and they are among the best bike fitters, running specialists, in the UK. They are smart folks, they just got a new Guru Fit Bike in their studio, they’re all crack bike fitters, and when they come over they all show up in their Vibram 5 Fingers and, bless their hearts, they run well and happily and injury free. I would not try to take them out of these shoes. Why would I? These folks have found prosperity and success in these shoes.

Accordingly, this is not going to disappear, nor should it. But I do think this pervasive movement toward getting everyone to adopt this paradigm is dying or maybe it’s already dead and, I think good riddance. Barefoot running is fast on a pace to correctly situate itself in alongside other tech paradigms and it will exist as a segment rather than a movement.

But it’s impact will continue to be felt. The Kinvara, that’s a movement. That’s a prototypical “natural” rather than “barefoot” shoe, it seems to me. This shoe, and the Brooks Green Silence (below), introduced a few years ago and a very interesting shoe at the time, a lot of people moved to shoes like this not only for racing but for everyday training. What I find interesting is they’re moving up to this from 5 Fingers, and down to this from structured shoes and even from orthotics. I hear things like, “I’ve drifted into training in race flats,” and “I've slowly transitioned to lower-drop neutral shoes and it made the knee troubles go away.”

Moving away from the shoe market and just to running theory for the moment, does this mean that runners were placed in structured constructs to begin with, but could have run fine in neutral shoes all along? Does it mean that structure was only necessary because of the bad running form a runner engaged in, and once he adopted good running form he didn’t need structure? Or that he just had an injury that eventually went away as all injuries do (except the last injury just before you stopped running?). Or that your structured shoe and/or orthosis was just bad, and it was a bad practitioner that got hold of you?

Or, it could be like that movie Awakenings, where you temporarily have a new lease on life but that’s going to go away. It might be that those who’ve needed structure, but who’ve moved to neutral or natural shoes commensurate with the adoption of proper running technique may find their ways back to structure once the need for structure reasserts itself, and assuming the right structured option presents itself to the runner.

I don’t know. But the point of this series is for me to make my best educated guess, and that guess is that the Kinvara/Green Silence motif is going to grow and remain a strong force in the tech running marketplace for years to come, and I think it’s because of a gift brought to us from the barefoot and natural movements: good running form. We now have the attention of runners in general. We are moving or have moved from, “Everybody will find his best technique” to “Stop overstriding.”

What does this mean for Asics which, I believe, has made shoes that work well for overstriders? Asics properly states that almost everybody is a heel striker. But it’s not that simple. First, if you did not ramp the shoe, would your heel still strike first? If you carved out the back end of the outsole, at an angle, would you still strike heel first? But to me, the most important question is, what do you weight most, the heel or the midfoot? When you ask that, the question almost becomes moot. If you strike with the heel but the midfoot is where all the action is – and where you need all the support, or the cushion, or whatever it is you need – then the fact that the heel strikes first is a detail. If you strike first at the midfoot, here’s a truth: you will nevertheless weight your heel. You cannot ignore the need for comfort and cushion in the heel.

My guess is that Newton will become more like Asics and that has already begun to happen. Newton correctly understands that its lug is placed where all the sex is. That’s the important part of the footplant. But its early shoes did not honor the need for cushion in the heel, and even a great runner like Craig Alexander is not going to just plant at the lug and push off and the heel of the shoe may as well not be there. Even if the entire world was made of midfoot strikers they will still compress the heel.

Conversely, Asics is going to become more like Newton. There are two ways Asics can do this. First, it can more ardently carve the back of the shoe (look at the Hoka shoes below) so that a midfoot striker doesn’t drag or catch at the heel, forcing a fait accompli. When Asics says, “everybody strikes at the heel,” yes! Of course! How many ladies are forefoot strikers when they wear pumps? If you make a shoe with 12mm or 15mm of drop, and you don’t carve out the back of the outsole and midsole, you create the reality you’re proving.

But Asics could keep its current geometries while still accommodating midfoot strikers just by tuning the strike point at the heel of the shoe. I don’t expect Asics to capitulate. But what I do think we’ll see from Asics, in the future, is an accommodation made for midfoot strikers. I think we see certain moves toward the Kinvara phenomenon from Asics, in the GEL LYTE33 3, where we have a 6mm drop (I find it notable that Asics is publishing forefoot and rearfoot thickness, yielding drop), EXCELL 33 3 (image below), and the entire Natural 33 line. I think Asics is going to find success with the confluence of its FluidAxis theme (written about in my previous installment) along with this lower-drop, free-form style.

Shoes like the Kinvara must have been motivators for the Natural 33 series, and this style or motif will get more and more popular, with runners moving up to it from the 5 Fingers and Minimus, and down to it from more structured shoes.

Large ramp numbers are out, moderate drop shoes are in. 15mm drops are out. 12mm drops are out. 6mm drops are in. I don’t know if zero drop is in anymore. I expect companies like Altra to come up a bit, and Asics to come down a bit, and everybody to meet in the 3mm to 7mm range. My bet is that this is the new normal.

And I hope this question of form is not lost. What makes these shoes work is the attachment to good form. I wrote about this in 2001 and the reaction to it ranged from ho-hum to how dare I interfere with anyone’s naturally arrived-upon best run technique, as if we should just leave everybody’s language alone too, and those who are naturally Chinese speakers would grow up speaking Chinese, and that the naturally-inclined Swahili speakers would develop speech patterns in that direction. We’ve come a long way and this attachment to running with good form – luckily most people who talk about what good form is agree with each other – pervades the discussion and allows these natural, low-drop shoes to exist.

Cushion

The problem with some of these shoes written about above – Asics Natural 33 series, Brooks’ Pure Project, and so forth – is that, yes, they’re light, and they’re soft and comfortable, but they are not soft enough for a lot of people. If you move from a 5 Fingers to a Pure Connect yes, it’s soft and comfortable. But if you move from that shoe to a Hoka Bondi, now THAT is comfortable. For some people, too soft, too comfortable, to the point of weird. Nonetheless, Hoka is rocketing up in market share – which is easy to do when your market share 4 years ago was zero – but if it continues on its trajectory it’s going to rival Saucony in and New Balance in technical running in 3 or 4 years. Any footwear company, any retailer, is silly not to take a hard look at this.

Cushion is coming. In 5 years you’re going to see a lot of companies making shoes with a lot of cushion sitting on a lot of platforms of slatwalls of run stores around this country and the world. What is not going to happen is Hoka retreating toward the industry middle in its cushioned shoes. What will happen is that Hoka will come toward the norm in this sense: it will fill categories it now does not fill. What I mean is, the Bondi will never not be the Bondi. It will never become a less cushioned shoe. But Hoka will fill the 8oz category and that shoe will not have the same cushion as the Bondi because it can’t and also be an 8oz shoe. But Hoka will never make a Kinvara, because that shoe is not sufficiently cushioned to be a Hoka.

Hoka might make a track shoe that somehow manages to stick a level of cushioning in it that rivals the Kinvara, but that’s still a cushioned shoe in Hoka’s parlance because, well, look at what track shoes look like now.

We’re going to get from less to more cushion either through shoe height or through innovative materials, or both. Last year Brooks introduced Super DNA, a material that provides 25% more cushioning than its (“game changing,” when announced in 2010) DNA midsole material, or its BioMoGo DNA, the latter a midsole material that biodegrades 50 times faster than other midsole materials. Cushion is even more important to a lot of people, apparently, than the health of the earth, which makes me believe that we’ll see a lot more cushion in the next 5 years.

This is going to create a new nomenclature for footwear. We are already on the way, because drop or ramp wasn’t in our lexicon, really, a decade ago. But what we will be wondering about is deflection per ounce, or the “crush-ounce” or the crush-inch-pound, or something that tells us how much deflection you get in that shoe, per square inch, per given amount of force, per shoe weight. Obviously I haven’t sufficiently thought this through or I would present that metric to you, but if you take a Bondi as an example, and the upcoming 8oz Clifton as another example, how much is the Clifton (image just above) “like” a Bondi in terms of cushion? Or, is it more like the Kinvara in cushion? Is it 20 percent of the way from a Kinvara to a Bondi, or 80 percent of the way? How might we state this in measurable terms? In 5 years we’ll have a metric for this. Maybe in 2 years. And shoe makers will pay attention to this metric and build shoes with this metric in mind.

No Cost Structure

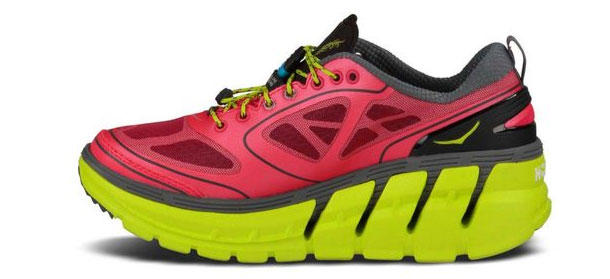

The problem with cushion is you need structure to manufacture this shoe even if you want to make an “unstructured,” i.e., natural or at least neutral, shoe. Imagine building the Empire State Building out of EVA. You’d have trouble on windy days, and you’d really have trouble if you wanted to put an Olympic swimming pool on the top floor. The trick is to build structure in a way that is of no real performance cost to the runner. I described this yesterday when I wrote of what I’m calling the midsole wrap: the midsole wrapping and supporting the upper, keeping the upper in place. If you made the Empire State Building out of EVA but you reinforced it with flying buttresses, as in medieval cathedrals – even if you make these flying buttresses out of EVA – then the building would have more structure. The Conquest (pictured just below) is Hoka’s medieval cathedral, and from the middle of the shoe back you can see its flying buttresses supporting the upper.

This structure comes at no cost to the runner. Anything you place under that runner’s foot – in the form of a higher density rubber or a plug or block – this costs the runner. In the just-previous installment of this series I quoted Dr. Benno Nigg who said, when speaking of orthotics, “a medial support, for instance, may produce an increase of knee joint loading in one person and a decrease in another person.” Could that not, to a lesser degree, even flow to structured shoes? Might the structure in the shoe work against the runner and his needs, by increasing a joint load it’s supposed to protect? Might this be why some people who need structure move away from a structured shoe to a neutral shoe because that structured shoe made things worse? But I digress.

I therefore think that no-cost, or low-cost, structure is that which does not cause an uneven compression of the shoe underfoot. I think this is what we’re going to see in the future. Maybe we’ll see this in ways Hoka does not now employ. I can imagine dual density or higher density EVA used, just, not underfoot. Might those “flying buttresses” be made of a higher density EVA? Might you be able to use less material if it were? I don’t know. But I predict that we’ll be moving away from what seem to me the really unnatural and unhelpful ways of granting structure to a shoe.

Lightweight outsoles

Strike pads or plates on the bottom of the shoe will become smaller and smaller as footwear companies take closer looks at wear patterns and only place these heavy outsole materials where they’re absolutely needed. Polyurethane is going, going gone as an outsole material. We now have compressive lightweight materials that have terrific abrasion resistance and good grip in wet conditions. Look for shoes with trademarked outsole materials like Solyte, Mogo, and RMAT. These materials will eventually give way to commodity pricing. Shoes are going to get lighter without suffering a performance reduction just in the getting rid of traditional outsoles. Shoes 3 or 4 years from now will, on average, be an ounce lighter than they were 2 years ago, with no performance or life span reduction. Of course, we may foul entire river systems in Asia and kill several cubic miles of ocean with the toxic outflow from the plants that make these materials, but, if your 10k PR goes down by 6.5 seconds then we’ll buy the shoe and look the other way.

Better sock liners

It sure seems to me that the one thing that has not changed at all in the last generation is the sock liner. This has advanced about as much, technologically, as the wadded up paper in the toes of the shoes once we pull them out of the box. What will change? I don’t know. But if I were to take a guess – which is what I’m doing now so here goes – I think we might end up with something like Superfeet in our shoes.

I’m arguing that this might happen but the calculus is against this, for a couple of reasons. First, price points for shoes are fiercely competitive. You’ve got your $95 shoe, your $120 shoe, your $150 shoe, and so on. Anything and everything is a cost center keeping you from hitting your target margin and price point, as a manufacturer. Nobody is pushing the sock liner. Nobody in your competitive set is coming out with a sock liner, as a feature, causing you to have to make competitive adjustment.

Also, retailers need this up-sell because it’s added revenue, and it’s an added specialty value. Anything that the store can do to customize the ride of your shoe helps inoculate the store from mail order.

Still, I think there’s a competitive advantage to be had. I would not be surprised to see an OE version of something approaching Superfeet (just above). I’m taking a flier here, but I’m guessing in 5 years the sock liner as we know it gives way to something more technical.

Rigid middles

The science of how you run and what a shoe needs to be in order to help you run is changing fast. Well, it’s not the science that’s changing, it’s the amount of people studying this versus a generation ago, and the interest from run shoe companies in what the science is. Used to be, you go into a footwear meeting at a shoe maker and the discussion was just in what features we can stick in what shoes to hit what price points. Enterprising footwear companes are rewinding this whole process, and asking questions like, “Why are we putting metal spikes in shoes meant for Mondo tracks?”

We’re going to stop seeing shoes that, when you look at them from the bottom, look like feet when you look at them from the bottom. As noted in the previous installment, Karhu, Hoka, Newton and other companies are keenly interested in how you get from foot plant to push off. This is going to be the biggest change we see in running shoes over the next years, I think. The heel isn’t going to change that much. The forefoot isn’t going to change that much. It’s the part in the middle, under the arch. That’s going to change.

The interesting question, to me, is how much this is going to change the really lightweight racing shoes, including track shoes. We’re already seeing. Look at Nike’s track spikes for sprinters (Superfly above). They have rigid plates connecting the front to the back of the shoe, spanning the entire arch area. I think this might just be the beginning of the understanding of the value in rigid midsections of high performance, high speed shoes. Mind, these rigid spikes may even be eschewed in 200m races because this rigidity may not be ideal for the turn. But I would be surprised if the traditional track spike for middle and long distance races do not undergo a big change in the next 5 to 7 years. They need to change.

But there’s another, strategic reason I think they’ll change. Track shoes have never been a profit center for any footwear company. But somebody is going to come along and realize that this is place you get brand loyalty, in cross country, which is once again the largest participatory sport in high school, and in high school track. This attention to younger runners is how Tiger (what became Asics) and Nike got their starts. When I was a high school tyke, we used to buy our Nikes and Tigers out of the back of the van of the local high school coach. There was no such thing as a run specialty store. So we got them how and where we could, and that’s how we did it.