Buying bike speed eventually gets pricey. What everybody learns, but nobody remembers, is that the cheapest way to get faster is to optimize your position on the bike. Let’s assume that there are two versions of you, each of which is equally fit and trim. What kind of speed improvements can one version of you enjoy, without spending any money or getting any fitter?

Let’s talk about free speed here, today, below.

The low-hanging fruit is bike position. For all the hand-wringing about products costing you hundreds or thousands of dollars that save you 40 grams here and 75 grams there, all that speed you buy only works on the 20-30 percent of drag for which your equipment is responsible. The other 70-80 percent of the drag is caused by your body. Don’t blame that 20 pounds of bike for all that drag; blame the 160 pounds of you.

There are two aspects of bike fit: fit coordinates and body posture. First there are your fit coordinates, and I mean your major coordinates. Whether road or tri (or MTB for that matter) we’re talking only about four numbers: saddle height; saddle fore/aft; cockpit distance; and handlebar elevation. That’s it. Certainly there a number of ways these numbers can be expressed: for example, by angular or x/y metrics; from the bottom bracket or from the saddle. But really what we’re talking about is where your saddle sits in space, and where your handlebars sit in space.

Let’s say that you’ve solved where your saddle and handlebars sit in space. What’s left to talk about?

Shrug

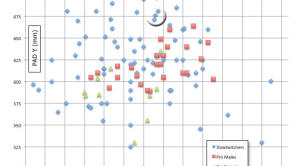

Damon Rinard and Nathan Barry, both of Cannondale, have investigated how bike posture and position affect drag. Above is Andy Potts racing Kona in 2015. Andy moved over to Cannondale for 2016. Let’s see what that might have meant for his position during the 2016 season. Nathan and Damon are each pretty high on the “shrug,” and that’s named for what it sounds like: Shrugging your shoulders. Lowering the position of your head without changing your rider position, i.e., without changing where your bike’s armrests sit in space, and narrowing your shoulders. The narrowing is likely the important part, since it reduces frontal area.

According to the Cannondale braintrust the “shrug” saves about 90 grams (measured at 30 mph or 43 km/h), which is huge. That converts to about 9 watts at normal ironman speeds, which extrapolates to 35 seconds or so over 40km, and you can do the math as to what this means over 56 or 112 miles.

This is easier said than done. If the shrug was the natural posture we wouldn’t have to “perform” it. We’d be performing it all the time without having to think about or concentrate on it. This means the shrug, while easy enough, does require practice, concentration and perhaps does exact some form of payment. The moral of the story: Shrug when you can: quiet stretches, straightaways, smooth downhills. Some is better than none.

Armrest Elevation

What I find interesting about the cumulative experience gleaned from Damon and Nathan is their view on the shrug combined with their numbers on armrest height. Damon says that on average riders save about 20 grams of drag for every centimeter the armrests are lowered. This means that the armrests would need to be lowered by more than 4cm – a very large amount – to equal the benefit you get from the shrug. I don’t know that I, a critic by nature, am prepared to accept that yet. But I find it an interesting data point.

Narrow the Elbows?

This is a favorite of pure time trialists. Triathletes rarely push their armrests together. How much benefit does this yield? Up to 50 grams, but that’s about the most that can be gotten under the best of circumstances, and it’s usually less than that. Narrowing elbows can come at a high cost. It’s quite uncomfortable to ride this way unless you’re rarely disposed to it.

To be sure, Damon Rinard says that elbow height and width doesn’t perfectly correlate across all athletes; the correlation is there but not strong. These are variables to test when you can, either in a wind tunnel or in the field, since you as an individual may or may not get these average benefits.

Clearly the shrug is the posture to adopt if you want the most benefit along with the least negative impact. This is Andy Potts again in the photo just above, in Kona this past year, 2016. One of the reasons Andy moved over to Cannondale was to avail himself of this kind of guidance. Andy’s fit was a combination of work with Cannondale, including wind tunnel tests, as well as work with Mat Steinmetz of 51 Speed Shop and GURU (Mat has been working with Andy's position for years).

Wind tunnel tests were about testing Andy’s aero parameter space. He combined that with his fitter to generate what we saw at Kona.

To me, just by looking at the images, Andy appears to be “hiding” a bit behind his hands, using the shrug (although it’s hard to tell because he’s looking down in that more recent photo). He also appears to have slightly raised his bars, and that wouldn’t surprise me considering how much value Nathan and Damon place on the shrug versus raising the aerobars or a centimeter or two.

So much goes into a race – training, fitness, taper, health, age – that you can’t draw a conclusion based on how Andy Potts or anyone performs on a given day. I saw Mark Allen give a talk a couple of years ago on how his bike position improved each year from 1989 to 1995, and from Mark’s perspective he finally had it dialed in that 1995 season. But Mark’s best season was 1989, so bike position isn’t everything.

Still, those looking for every edge can take comfort in the knowledge that not all speed on the bike costs money. Back to those two versions of you, each of which is equally fit and trim: An extremely fast, and expensive, bike frame may be fewer than 100 grams faster than a good but modestly priced frame. The optimized version of “you” maybe be worth more than any frame upgrade you might make, at any price you might be willing to pay.