Welcome to Triathlon! Have you found your second job yet?

Ha! Just Kidding! But look, this sport can seem expensive. That doesn’t mean it needs to be expensive. Let’s talk about the tri bikes that are semi-pricey but not ridiculously so. What am I talking about? New, fully-featured tri bikes that cost in the upper-$2000s complete and, with a few added do-dads, would be good enough so that anyone who won the Hawaiian Ironman would win it anyway were he or she on any of these bikes.

He didn’t just say that?! Yes, he did. Well, then, why should anyone buy a bike costing more than entry level? Why indeed? These bikes are just not that much slower than the bikes costing 3 to 5 times as much. Still, the entry level tri bikes today don’t have everything the more expensive bikes have.

In fact, let’s take Quintana Roo’s bikes (my old job!). This company’s best selling tri bike is its PR6, and will cost you double or more than the QR I’m writing about today. It’s got a number of upgrades, especially the disc brake version if you’re into that sort of thing (which I am). But the PR3 is a heckuva bike for the money. (The image above is a detail from the PR3, which costs $2,599.)

I’ll write about each of these bikes individually, each in its own review, upcoming. But today I want to lay down a few markers, for reference.

Entry Level Plus?

What is Entry Level Plus, and how dare I use the term “entry level” to describe a bike costing between $2,500 to $2,999?

You can buy a very good tri bike – and let’s use Felt as an example – for under-$2000. That’s truly the entry level. The bikes I’m writing about here, in this series, are the entry level versions of bikes that could be souped up into Ironman-win-level bikes. They each have framesets that are so close to the best that you just won’t give up that much as long as you’re aboard these frames, and assuming you’re well-positioned and the bikes are comfortable.

Here, over the next week, I’m going to show you bikes that won’t cause you to whine on our Reader Forum about the horrible purchase you made; that don’t fit; where the tires you want to put in them won’t fit; where you have to replace a third of the parts; that are uncomfortable every place you touch them with your body.

In these “pages" I will show you the cheapest bikes you could, literally, win a top caliber race aboard (like the Felt IA 16 just above). Just, there are certain things these bikes have in common, that pass muster. I’m going to tell you now what those imperatives are; to arm you with some axioms to guide you, so that you can choose wisely.

These Bikes Are Comfortable!

What’s a superbike? In our parlance it’s a bike (tri bike usually) that’s fully integrated, meaning the stem, the aerobar, all of it’s smooshed together in one seamless construct, kind of like a motorcycle. A “mortal” bike is a tri bike that uses a traditional stem. Superbikes are better. Right? Well, not always! Bike companies that build their own aerobars aren’t necessarily the best aerobar makers. Most of the time their aerobars are not very adjustable.

For example, the Scott Plasma Premium is a really nice bike (I built one up, soup to nuts, several months ago and it's a terrific bike!), and the aerobar is adjustable a whole big bunch. Heightwise. But lengthwise? Not so much. The Giant Trinity Advanced Pro has twice the length adjustability of the Plasma Premium, but only half the height adjustment range.

This makes mortal bikes (like the Cervelo P2 above) a little more flexible, because you can change both the aerobar and the stem. You can change the stem as well on some superbikes – Trek has 6 stems for its Speed Concept – but this is rare.

When the Bar is the Primary Purchase

Profile Design is getting ready to announce a major revision of its aerobar lineup. Whether this will sufficiently reverberate elsewhere I cannot say, but it will on Slowtwitch. Lecture mode on: Too often, you guys major in the minors. With aerobars, there is a tendency to be cavalier about something very important. Let me give you an example…

What I hear, often, in bike fit, as I move a person forward, is, “I feel a lot of weight coming down on the front of the bike.” As in, you’re uncomfortable. Okay. In some cases I may reply with: “Would you rather than weight be coming down on your saddle?”

That sheds new light on the subject, doesn’t it? This is why “contact points” are so important. Weight has to come down somewhere. This makes the aerobar as important as the saddle, not just because of its own comfort requirement, but because moving the cockpit forward may grant power; allow the rider to be lower (which usually means more aero); and transfer weight off the saddle. It may also make the aerobar and saddle more important than how aero your helmet, your brakes or your wheels are. Whether your tires roll quite as fast as other tires. And so on.

There’s a second reason why Profile Design’s revamping of its line is important: There’s a new, very cool, low-profile option that is low-priced (spy shot above). Previously, the really good low-profile bars were pricey. I often would say to someone I fit, “Your best purchase is a TriRig Alpha X.” [Now Alpha One.] "But wait!” you say. "That’s not a bike! I want to know which bike to buy!" And the answer is, there is no bike for you unless you start with this bar or something like it, because your position is “long” and “low".

A bike such as the Scott Plasma Premium just couldn’t be ridden in a long and low position; nor other superbikes that use bars you can’t swap out. Mortal bike to the rescue! Just, we’ll soon have a bar available that gives you the low profile option at a low Profile price (get it, low Profile price!), and with the armrest adjustability, ergonomics, comfort, ability to choose a variety of extension shapes and so forth.

This means mortal bikes in the entry level price point can now remain in the entry level price point even with a bar swap. (We’ll talk about Zipp’s low profile option as well.)

Small Bikes

I have two gripes with the bikes I'll be writing about. Here's the first.

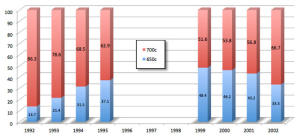

The single most harmful set of fake facts perpetrated on the cycling world in my lifetime is the notion – across all of cycling disciplines – that the larger the wheel the more desirable the wheel. And, women are equally culpable in this because, yes, the men you relied upon for advice told you that 700c was better, and you believed them!

As I write this I’m hoping to receive an inventory of 45cm and 48cm framesets in the entry level price point made with 650c wheels (26” wheels, 571mm bead diameter). Above is an image of the sort of bike I'm talking about, which I used to make, but this bike is 25 years old.

It is true that Canyon will be making women’s specific road race bike with the currently more favorable (because of MTB and gravel) 27.5” wheel (584mm bead diameter). Fine. Shrewd. Much better than the 700c (622mm bead diameter). Either is okay. Just, you’re more likely to find 650c as mortal bike leftovers and closeouts, often as bare frames.

PremierBike is cutting a 650c mold, and that company is going to carve market share (they let me see the CAD drawing, so, of course, you get to see it!). But that bike is a discussion for another day.

They fit!

Because of the bars and front end configs, because of their geometries, the bikes I’m going to list will fit you! (If you’re like most folks.) I’m kind of a stickler for bikes that match you, instead of you contorting yourself to match the bike (or contorting the bike via some strange stem and spacer package.)

They shift! They stop! They adjust!

Used to be, shifting and stopping were imperatives that bike makers had to honor. Not so much anymore. Happily, entry level tri bikes – at least the bikes I’ll be writing about – do all that stuff pretty reliably. And, you can work on them. Adjust them. Pack them into bike boxes for travel. Raise and lower the saddle height without breaking something. Get the tilt of the saddle exactly right. You know, meet the arcane unreasonable demands of persnickety consumers.

Where Did [Blank] go?

As I write about these bikes over the next week, you’ll note the absence of some players. What about Cannondale? And so on. Fact is, some of these companies have either abandoned the market altogether or they’re keeping their plans close to the vest (but it's pretty late, if that's the strategy!).

Speaking of Cannondale, who knows? Its sponsored team at Abu Dhabi was just sighted using a new aero disc brake road bike. And this is the way Cannondale typically “leaks”. Same thing with Andy Potts a couple of years ago with the disc brake Superslice. But, that Superslice never really showed up on the market, that I could see. Cannondale has a way of saying nothing until it has something to announce, and I get that. The point is, unless I am told something I don't yet know, Cannondale doesn't have a tri bike I can write to you about right now. That doesn't mean it won't have one next week.

What Could Change (and I Wouldn’t Complain)

I have one gripe about these bikes, and it revolves around the type of armrest and aerobar pad bracket used. Most of the bikes in this category rely on a style of armrest bracket popularized by Profile Design years ago: the J2 Bracket shown below. Quintana Roo, Cervelo and Felt all use this kind of bracket, where the armrest bolts onto the extension, which in turn slides into the bracket that attaches the extension to the pursuit bar.

Yes, this system allows for more adustability than just about any other. But, there are limitations to its design. It’s harder to adjust, because adjustment is always several steps (move the extension back and forth, tighten it, then loosen and move the armrest back and forth to normalize for the difference, then rotate the armrest around its fulcrum to get that right). But that’s an annoyance. My real problem is that it’s a fundamentally worse design, from an engineering point of view, because of the stress it places on the brackets and the extension. The rider’s weight, cantilevered off to the side, means significant torque needs to be applied to both the clamps into which the extensions slide to keep the extension from rotating about its axis under that stress.

This in turn limits the tech you can use in the extension. Forget making that out of carbon! Both Profile Design and Blackwell (and perhaps others I’m forgetting) learned that lesson. Or, if you do make it out of carbon you must beef it up enough to moot the weight savings.

Having said that, Felt successfully does it. the IA FRD (as one example) uses this motif with its ƒ-Bend carbon fiber 3-position extensions handlebar. So, when I get around to writing about this year’s IA fully integrated superbike I’ll revisit this.

Just, I’m much happier with Profile Design’s J4 and J5 brackets, and it’s F35 and F40 armrests. In the case of the QR and Cervelo bikes I’ll be writing about, they’re halfway there. Each of their bikes in this category, as currently spec’d, use the F35 armrest (good) on the J2 bracket (which I’d like to see upgraded by next year). Both Profile Design and Zipp (to name two) have migrated to affordable bars where the armrests and extensions all attach to a single clamp (my preference).