Cliff Rigsbee R.I.P.

Cliff Rigsbee, an outstanding age group triathlete for 35 years, died June 16 from injuries he sustained during a rescue watercraft training accident near Diamond Head, Oahu last week.

Rigsbee, 63, a 21-year veteran of the Honolulu Fire Department, was on a sled being towed by a jet ski operated by a fellow member of Engine Company 7 in rough surf about 10:45 AM Tuesday, June 14.

In a news conference Wednesday June 15, Honolulu Fire Chief Manuel Neves said that Rigsbee was riding behind the watercraft when the two men hit a big wave at a surf break known as Suicides. After the wave passed, the operator of the watercraft looked back and saw Rigsbee floating unconscious in the water.

Rigsbee was brought to shore by firefighters and Ocean Safety personnel. He was treated on shore by paramedics and taken to Straub Medical Center in critical condition where he died late Thursday night.

Rigsbee joined the fire department in July 1995 and was promoted to Fire Fighter 3 in October 2004. While off duty in October 2012, he rescued an injured hiker on the Koko Crater Trail and carried her down from the top of the trail to waiting fire rescue personnel and paramedics, Neves said.

Rigsbee spent much of his 21-year career in the Honolulu Fire Department in the training bureau. “He was so knowledgeable,” said Neves. “He served in our medical branch helping teach all of the firefighters about medical techniques. His legacy will carry on for many years because of all the folks he mentored throughout the department and the skills and knowledge he bestowed upon all of us.”

Triathlon success

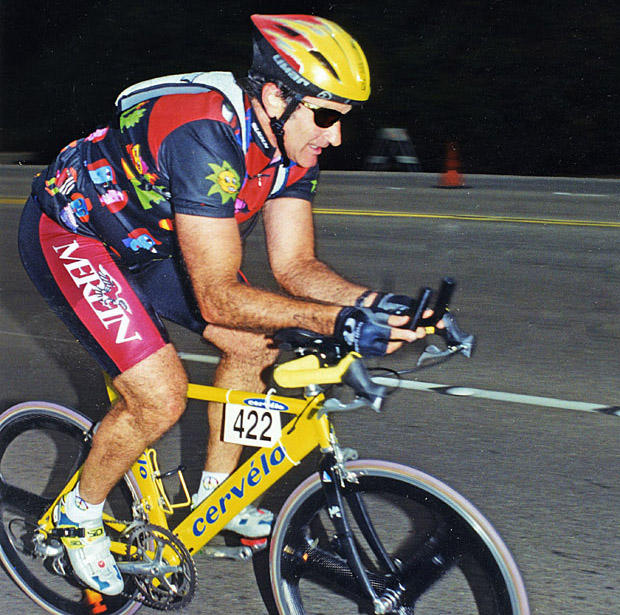

Rigsbee was a talented age group triathlete who had six age group wins at the Ironman World Championship, was a USA Triathlon National Masters Triathlon champion, was first overall age grouper at the 1991 Wildflower long course, won the Tinman Triathlon twice and finished 5th overall at the 1998 Ultraman World Championship in Hawaii.

In 1992 at Kona he finished 26th overall and won the 35-39 age group in a personal record time of 9:01:34. That performance gave him hope he might become the first man 40 and above to break the 9 hour barrier at Kona. In his first crack at 40-plus record in 1993, he finished 67th overall and won 40-44 in 9:10:47. In 1994, Dave Scott beat Rigsbee to the 40-year-old sub-9 mark record in 8:24:32 for his second place finish to Greg Welch. Rigsbee finished 34th overall and won 40-44 and improved his time to 9:10:22 but fell short of the sub-9 hour dream.

Inspirational coach and caring mentor

Rigsbee was a key figure in the Hawaiian triathlon and endurance sports community where he also served as a coach, training partner and adviser to countless fellow athletes.

“He was my primary trainer and coach and mentor,” said former professional triathlete Debbie Hornsby. “He had such a special place in my heart and with the people involved in the triathlon community and the athletic community."

Loren Kollar was one of many everyman triathletes coached by the man with lofty talents while maintaining the ultimate everyman attitude.

“Some people in your life change who you are,” wrote Kollar on Facebook June 17. “I had never done one athletic thing when I showed up at HR Training with a 5 speed and no goggles. Cliff promptly told me I was going to need new everything. And that's what I got. A new life, a new me. Personally I was fighting to keep my head above water, and now I was physically too. The hours of talks we had through long runs and bike rides are always with me. I don't have the words to express my appreciation and love for you Cliff. Yesterday I found out my friend, my coach, my hero was gone. Earlier that day I had been trudging through a long run and Cliff’s quiet footsteps and standing tall had got me to the end of another sufferfest. You are always with me. Thank you for helping me see who I can be and who I want to be. I love you with all my heart, my friend.”

Background

Cliff Rigsbee was born January 9, 1953 and attended Greenfield [Indiana] Central High School where he was a pole vaulter and ran 440 on the relay team in track, and did the 200 IM (2:09) and 100 freestyle and 100 breast stroke for the swim team. He received a swim scholarship to Idaho State University in Pocatello and competed until the program was dropped and so he switched to a water polo club team. After college he moved to Boise, Idaho where he was selling valves and fittings in 1980 when he saw the television coverage of Ironman Hawaii.

“There were only 108 people who did it and I turned to a friend of mine and said ‘Wait a minute!’ Being quite decadent and the like with beers and whatever, I said ‘When I can afford it, I will go do that one of these days.’

“My friend Bert Hansen said, ‘What? You think you can do that?’ I said, ‘Bert, you don’t know. I was an athlete in high school and college.’ I always knew I was better than average no matter what I did as an athlete. Bert said, ‘Well, I’ll help you get there.’”

Rigsbee was sparked by doubters. “I sent my entry form in and friends of mine and people I didn't even know said, ‘You’re out of yer mind. You can’t do that!’ That probably meant more to me than anything – telling me I can’t do something. I have always been somewhat of a rebel when it comes to that type of thing.”

On February 14, 1981 Rigsbee was 11th out of the water in 59 minutes and was off on a lifetime journey in the sport.

Irrepressible spirit

From the start, Rigsbee may have been ambitious in his personal quest, but he was personally humble and was a positive thinker and enthusiastic supporter of anyone who shared the triathlon dream. “The people who first of all said I couldn’t do it, they placed me up on this pedestal,” said Rigsbee. “They said, ‘Aw, I could never…’ And I just said, ‘Whoa! Time out! I am getting down off your pedestal. This is bullshit. This is not the case. You can do this. C’mere. Let me help you. You’re a person. Yes! Come on! Let me show you that you can do this.’ To this day when somebody says, ‘I can never do the Ironman,’ I say, ‘No, the only reason you can’t do it is because you don't want to do it. If you want to do it, I’ll help you get there.”

For all his racing successes, Rigsbee says he was most proud of persevering on a bad day at Kona. In 1990, he was out of shape with five weeks to go when he tried to make up fitness fast, jumping from 100 to 250 miles a week on the bike and from 25 to 50 miles a week on the run. “When I got to the Ironman,” said Rigsbee, “mentally I didn’t have it any more. My body said, ‘You are killing me. Quit. Stop. Don't! You can’t go any more. After five weeks you keep asking me to do this!’ I was fighting myself physically and mentally.”

After a decent swim and a difficult bike, he started the run and the inner voice started to shout, “‘What am I doing out here?’ I told myself I would not do this when it wasn’t fun. And this was not even close to being fun. I realized I am having a miserable time. I am fighting myself and I was running alone.’”

Then Rigsbee found another, outer voice starting to fight back. “One of the things that always irritated me about people that I have competed against or with – they say, ‘Well, I dropped out because I wasn’t going to have a PR.’ And I just told myself, ‘I am not going to do that. I am going to finish. I am running along Alii Drive and wanting to quit and I just said, ‘You know you have never quit.’ And the inner voice is saying, ‘Aw, but it’s killing you.’ And then the outer is saying, ‘Oh, but you haven’t surrendered yet.’ The inner is saying, ‘You better quit. ’ It was back and forth and back and forth. And the next thing I know I am on the Queen K highway and I am saying, ‘Why quit now?’ So I finished. And it wasn’t a spectacular year. I went 10:22 – a slow race. It just meant a lot to me because it was an honor to finish.”

Rigsbee’s son Cliff Jr. cited a Facebook post by Harry Lopez which described his father’s recent 130 mile bike workout ride with much younger, stronger men. The young guns took off in the middle of the ride and thought they dropped the old man. But at the end of the ride, Rigsbee dialed it up and “murdered them on the climb up Makapuu and made it back to town well before anyone else.”

“I found this random post online about my dad,” wrote the son. “Funny how this is exactly how he was – he could ride/run/swim circles around all of them (usually half his age) even when they were riding in a group and taking turns pulling each other and he was a lone wolf. Love this. Dad – you were in a league of your own and you lived life doing what you loved. Love you."