Mark Allen on Nice

For the time in which he raced and what he accomplished over his career, his breadth and range, and how his times have stood up, I still consider Mark Allen the greatest multisport athlete – and one of the world’s great endurance athletes – of all time. In light of the recent decision to plant the 2019 Ironman 70.3 World Championship in the location where Mark had a signature string of victories I thought it might be interesting to see what he had to say about Nice, France.

DAN EMPFIELD: I feel like I’m locked in an annual cycle, like a hibernating bear. Every February or March my blood chemistry changes and I start to think about the Cote d’Azur, the casino in Monte Carlo, the medieval villages on hillsides and the roads through them where I loved riding my bike and the old Nice Triathlon. It’s not logical because I haven’t been there in 25 years. But every Spring I get it. Maybe you’re over it or you never felt that way.

MARK ALLEN: I don’t have the same yearly itch but I do have the memory of the entire environment in and around Nice. It happens at random when something reminds me of those places and experiences that are so precious.

As an example there are days when the blue of the Mediterranean along the shore out in front of the Negresco Hotel is like nowhere else. It’s this powdery baby blue you only see in Nice. That comes back to me every time I’m somewhere with really blue water. I think, yes, it’s blue but it’s not Nice blue!

I also get those pangs for Nice when I see mopeds, which there are not a lot of where I live. I get a flashback to the endless string of them with the cars along the Promenade Des Anglais day and night.

But what I miss most is the riding. We just don’t have roads like in the Maritime Alps where the bike course went. Small, winding, steep, 180-degree turns, houses right up to the road in tiny villages along the way. Loved that time and miss riding those roads.

DE: I interviewed Lance Armstrong a couple of months ago and he’s reflective about his future in endurance sport. There is a proper place in sport for him and smarter people than I will decide what that is. But he said one thing, that if he could be given the opportunity to race Ironman France… Not Kona. France. There is something about that place, the Maritime Alps, it’s just not like any other. When you wrote The Art of Competition it was with a little Thoreau and Emerson, so I’m going to put you on the spot and ask you what that place, those roads, mean to you in Emersonian terms.

MA: Those roads are slow. From cars to bikes you cannot go fast. But that slowness isn’t just about the roads. The pace in the villages is not governed by high speed Internet but by life rhythms that have built their stories over hundreds of years. Every hamlet has a drinking fountain fed by water that’s taken eons to bubble up.

Maybe if I lived there all the time that out-of-time feeling would wear off. But I doubt it. It’s sweet. Life is still taking its time in the Maritime Alps. I knew it was something precious because even in the race, in the heat of competition when I was suffering, I’d catch myself looking around just trying to take it all in.

DE: You won Ironman 6 times. You won the Nice Triathlon 10 times. If you could have your jersey retired in one stadium, for one franchise, which would it be?

MA: That’s like asking a parent which of his two children he loves more. You love them both but for very different reasons. That’s how I am with Nice and Hawaii. I’ll defend both as being where I had my greatest races of my career but for very different reasons.

Hawaii was much more complex to win. The heat, wind, humidity and the energy of the Island. It did more to reveal me to myself than any other race. So the lessons learned on any given day were more intense than in Nice. That said, Nice had its own complexity. Winning it ten years in ten starts surpasses anything I did in Kona. Those years In Nice taught me more about racing than anywhere else.

Nice forced me to learn me how to keep going even with a complete meltdown, as in 1983 when I walked, fell to the ground late in the run, with a charging Dave Scott closing in. I learned how to go beyond my fitness and pull a performance out. The 1992 race against Yves Cordier when I passed him with fewer than 400 meters to go. Nice taught me how to use slow ratcheting up speed to break an opponent even if I knew it could break me first, the head-to-head run with Simon Lessing in 1993.

DE: The sport has locked itself into either the full or half distance. I always felt the Nice distance was special. You could race it, not just survive it. A guy like Ric Wells or George Hoover could win that race, even though it’s two-thirds a full distance. That was kind of the line of demarcation, the natural meeting place between sprint and distance, where you could race a Simon Lessing – which you did – and neither was racing the other’s distance. Do you think we’re good now with the half and full distances or do you think it’s a big loss not having more 125k bike and 30k run courses on the schedule?

MA: It is a shame that the Nice distance isn’t more common. The race took roughly 5-and-a-half to 6 hours to complete for the top folks. That is right at the limit where you switch from needing more speed to needing more endurance. So it’s right at that sweet spot where it was essential to have both. If you were simply fast you didn’t have any hope of holding it together to the very end. If you were endurance-dominant you would just be off the back and never be a true factor for the win. Maybe we need a new word for what it took: Speedurance!

I loved that combination. Just when I thought I couldn’t push any harder I’d up it a notch and realize I could hold it. But I could do that because I had the speed to go fast and the endurance to hold that speed. It’s just short enough that I was not thinking about survival. I was always trying to manage the intensity pain of going really hard but not the breakdown pain that I got in an Ironman.

When I raced there I felt like the entire day was like winding a spring tighter and tighter until it was just about ready to snap. I’d go hard on the swim, but not all out for sure. It needed patience and pacing. I’d push hard on the bike in the hills but really tried to recover on the descents. On the long gradual return on the flat stretch along the river back into town I’d start really tightening the spring. I’d keep squeezing the pace through the first half of the out-and-back run until it felt like it was time. Then I’d just let it loose. I figured for about 10 miles all the way back to the finish I’d turn the race back into pure speed. Forget the endurance at that point! Yes, it’s a truly great race distance that tests for balance between being fast and having endurance.

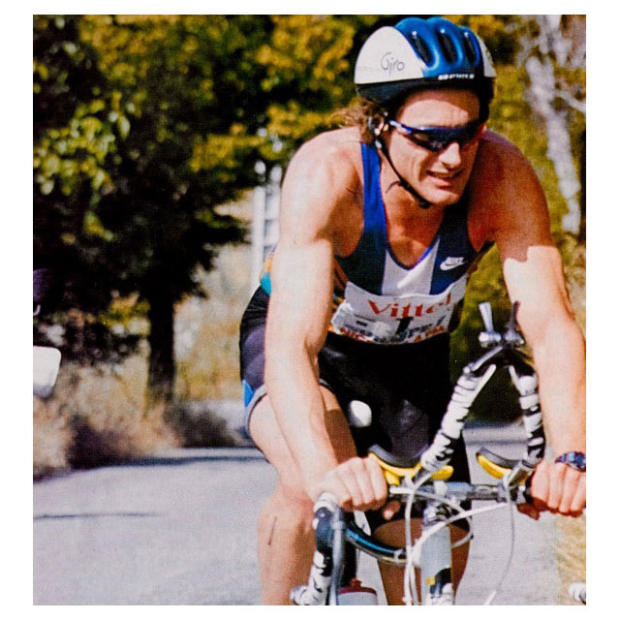

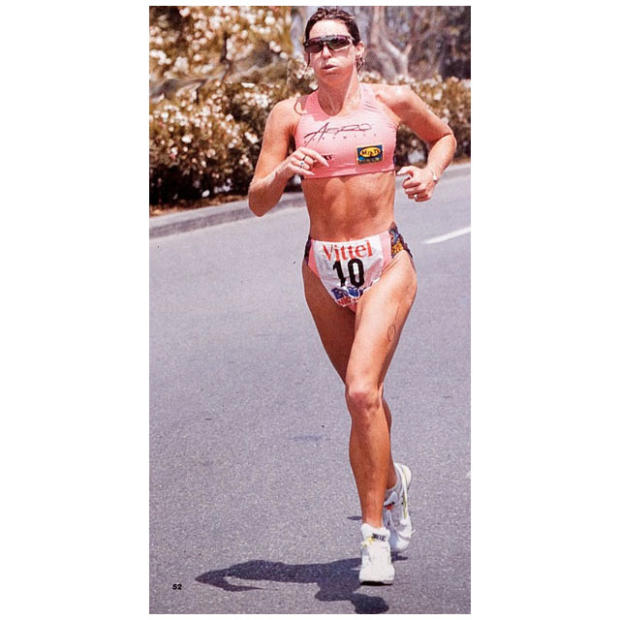

[I asked former publisher of 220 Magazine John Lillie if he had anything in his possession from the old Nice Triathlon. The images here are what John provided, of Mark Allen and Paula Newby Fraser racing in Nice at least 25 years ago.]

Start the discussion at forum.slowtwitch.com