Introducing Our Sports Nutrition Series

I’m about to commence a series on nutrition for training and racing. Nutrition, in this context, does not cover what you eat for breakfast, lunch and dinner, but the water, fuel, electrolytes and other substances that you consume during training and racing. I’m not even going to talk about pre- and post-workout nutrition. This is just the stuff that goes down your gullet when you’re engaged in an endurance athletic activity.

This is going to be a lengthy series and this is the first article in that series. The concepts and language might get pretty heavy as we get into this, in spite of my own, and Slowtwitch editors’, attempts to deconstruct my tendencies toward obtuse academic framing. (Editor's note: a work in progress.)

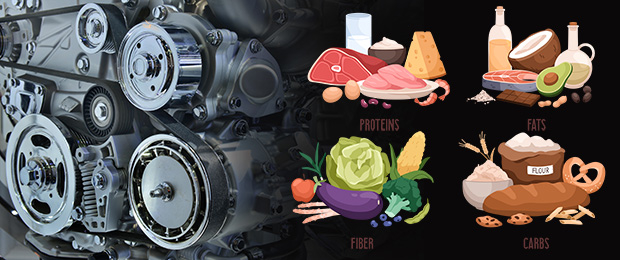

What you’ll read today are mostly definitions and information that will help us speak the same language in the future. For example, a calorie is a measure of heat. It’s the heat it takes to raise 1 gram of water 1°C. But heat and energy are in this context interchangeable. Calories are, as we know, a method of quantifying the energy we consume and that energy powers our muscles, just like gas powers our cars. In fact, it’s just like that, because in our bodies and in our cars it’s carbon plus oxygen, in a chemical reaction, that produces energy.

But I prefer to talk about grams of carbohydrates. What you need to know is that 1 gram of carbohydrate = 4 calories. When I write about 90 grams of carbs as the heretofore considered upper limit that our bodies can absorb (I will challenge that view, as you will see), if you are more familiar with calories per hour (technically it’s, kcal/hr), you can multiply 90 x 4 and you get the number in your language (360kCal/hr).

So, here are some basics to get us started.

Calories are a measure of energy. We need energy to propel ourselves forward in endurance sports. That energy has to come from somewhere. Thankfully “energy” can be in the form of stored “potential” energy, or in the form of physical “kinetic” energy and even more thankfully for us and our sporting endeavors, the two types of energy are interchangeable and our bodies are essentially energy interchange machines.

Your body turns potential energy stored in the form of organic molecules into kinetic energy through hundreds of interconnected molecular machine systems within it. That’s an elaborate way to say, your body burns stuff and uses it to produce motion. Much like a car engine. Also much like a car engine, your body produces a bunch of heat while it does all these chemical reactions. In a purely physical sense, endurance athletes are a bag of chemicals organized into a soupy mixture of compartments all with their own parts designed to propel the whole body forward as fast as possible for as long as possible.

One example of such a compartment in your body is your muscles. They’re like the engine. Muscles make you go. They produce the forces, using the fuel delivered to them (caveat: they’re a weird type of engine that also stores some of its own energy internally. You may have heard of it: glycogen. Your car engine doesn’t store fuel in it. Your muscles do. More on fuel tanks later.) Your bones are like the drivetrain. That’s the stuff that connects the muscles to the road and applies their forces to something else to actually create movement. Bones transmit the engine work into making you actually move forward. Your cardiovascular system is like the fuel lines and fuel pump (heart). They deliver fuel to the muscles. We’ll ignore the other 100 functions of your cardiovascular system for now.

Your brain is like the computer of your car (if it’s newer than my car). It tells the rest of the system what to do and how and when to do it. Your brain needs its own energy too, as does your cardiovascular system. Thankfully the cardiovascular system is well-protected by our bodies such that it pretty much won’t run low on energy, ever. However, your brain can run a bit low, though it’s usually pretty well-protected from catastrophe. But, importantly, when your brain does run low on fuel, your computer gets sluggish, and when that happens, the rest of your body, especially your muscles (the engine) will also be sluggish because the computer is what tells them what to do and how to do it.

Let’s move on from the car analogy for now, and back to energy. Each of those subsystems need energy. Especially your muscles and brain. If either falls short of getting the energy it needs, they’re going to slow down. A lot. And neither your muscles, nor your brain, will ever take in more energy than they need while you're exercising, so the fuel lines (blood vessels) have to constantly be delivering enough energy to meet the instantaneous demands of the muscles and brain.

So, back to the car analogy for a moment, here’s the high level overview.

–Your muscles are the engine.

–Your skeletal system is the drive train.

–Your heart is like a fuel pump.

–Your blood vessels are like fuel lines that the heart uses to pump the fuel from the tanks to the engine, the muscles.

–And then there are fuel tanks.

Let’s talk about the fuel tanks, because they have implications for how we think about fueling. If you don’t understand the fuel tank situation, you’re going to get fueling wrong. In a car, it’s simple. There’s a tank. It stores the fuel. End of story.

In humans, it’s a little more complicated because there’s more like four physical tanks. This concept is going to feel a little new, so, seatbelts on.

–You have 3 primary internal fuel tanks and one ridiculously finicky 4th tank. Turns out, that 4th tank is kind of a big deal.

–Tank number 1: Muscles have their own small internal tank. It’s full of glycogen, a carb.

–Tank number 2: Your liver is a small tank too. The liver stores carbs. (When it’s acting as a tank. It does other things, too, but we’ll get to that later, too.)

–Your fat tissue is a fuel tank. It’s got, you guessed it, fat in it. Unfortunately, while this tank is massive, and exists everywhere all over your body, it’s a slow-burn kind of fuel so it can’t keep up with the demands of your engine all by itself. It’s also very slightly less efficient so your engine (muscles) has to work ever-so-slightly harder to burn it.

–Your saving grace is a 4th, very very finicky, auxiliary fuel tank. Your gut. I’ll explain what I mean, below. It’s worth understanding.

Walk with me for a moment into your imagination. Imagine you have a five gallon bucket strapped to the hood of your car. Actually, no, let’s not use straps. Let’s use duct tape. You have a 5 gallon bucket duct taped to the hood of your car. Now, imagine there’s a hose running from that tank to your fuel pump, which can pump the fuel to the engine where it gets burned. That hose is the size of a coffee straw. You can pour your duct taped bucket full of fuel and it will just barely provide adequate fuel for your car to go forever, even as the other tanks are running on empty, with one caveat: you have to have a tanker truck full of fuel driving next to you to continuously add fuel to your duct taped hood-bucket tank.

You can go forever using it, but it’s one heck of a finicky system to get fuel into your car. If you over-pour and fill that car-hood-bucket too full, it’ll splash gasoline all over your running engine and light everything on fire. If you hit the gas hard while it’s ¾ full, you’re going to splash gasoline everywhere and do the same thing. Crash and burn. If you put the wrong fuel in it, it’ll clog the hose and slow down the delivery of fuel through it’s meager little hose. If you overfill it too much and drive real fast, you can even dislodge the bucket and rip the hose from the fuel pump connection, meaning you’re not getting any fuel at all and you’ll very soon be stopped in your tracks.

In the same way, if you overfill your gut, it’s going to revolt and stop you in your tracks. If you punch up how hard you’re exerting yourself all of a sudden, your gut will do the same thing if it’s even close to being full. And finally, if you intake stuff that clogs up your guts mechanism of delivering fuel to the fuel lines, then you can’t get fuel delivered as quickly… which means a fuller bucket, and more risk of imminent crash and burn.

Let’s stop here for a moment and present a new word you’ll hear me throw around regularly. Intake. Intake is what you pour in that bucket. Intake just means, the stuff you put in your mouth, and swallow, sending it to your duct-taped-hood-bucket, that serves as your finicky auxiliary fuel tank.

While this is a silly analogy, it is truly representative of the way our bodies work during exercise. The tiny hose represents the lining of your small intestine, which is responsible for slowly leaking fuel into your blood stream, your fuel lines. That slow dripping, or “titration” (a chemistry lab term which means “slow adding”), of fuel from bucket to fuel lines, or from gut to bloodstream, is called “absorption.” Absorption refers to the process of stuff going from your gut, to your bloodstream, and is rate-limited by a whole host of things. That “whole host of things” in our car analogy here is the tiny hose leading from the bucket to the fuel lines. That tiny hose represents all the cellular machinery that actually transmits gut contents into your blood. Transporter proteins. Fluid channels. Cell membranes. All details we can store away in our imagination for later.

It is with this finicky system that we humans operate. We have limited onboard fuel (carbs), a poor secondary fuel (fats) which work only for slow driving, or only provide a portion of the energy we need for faster driving, and a small auxiliary fuel tank that is as finicky as you can imagine. And the faster we drive, the more perilous it becomes.

We put up with this temperamental system because we have to. We need the energy. It has to come from somewhere. We’ll look at the specific sources of energy, and how to talk about them, think about them, and implement them, in the next article.

Start the discussion at forum.slowtwitch.com