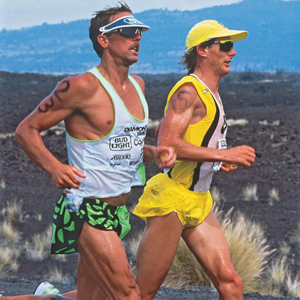

Iron War

Matt Fitzgerald pivots his book, Iron War, around a moment in history: October 14, 1989, 2:59 pm Hawaii-Aleutian Time. This is the moment when—7 hours, 58 minutes and 2 seconds into what may be the greatest race two men have ever run—one begins to prevail.

Iron War commences with that moment, then immediately pans out to provide the landscape that brought the Ironman, Mark Allen, and Dave Scott, to that place, under that hot sun, on that afternoon.

While not a biography, the book hits its stride early in, as it begins with a recounting of Dave Scott's formative years. Even for those of us who've known these two men for a generation—and I checked with several of them for the purpose of this review—we all learned an awful lot we didn't know. Each man has guarded his privacy, and husbanded his image, as we all wish we had the discipline to do.

Consequently, the unwrapping, and the public presentation, of the lives of these two is unprecedented in each of their experiences, and unprecedented in our sport. Neither Mark nor Dave participated in this book, and neither is happy that the book is published. Their lack of cooperation with its author may have even improved Iron War, as neither man was there to mitigate any of the narrative that exposes the flaws and warts that conspired to make them the men that gave us that precious and seminal moment.

No man wants his insides flayed for fan pleasure. And if there's one public activity where a professional can truly say, "I didn't sign up for this," it's certainly triathlon or, at least, it was in the early 80s. No actor, or professional main-sport athlete, or politician, can claim he had no idea there were those who'd seek to write about his private life. But triathlon, 30 years ago, was not an activity to which one aspired as a profession. You literally went from asking, "What is a triathlon?" to earning your living as a professional triathlete, in 18 months. Still, the heroes that create a culture's mythology cannot bottle it, and dole it out at their pleasure. Dave and Mark are our heroes, and this is our mythology, just as much as Bannister's mile is to runners everywhere.

Two lengthy sections in Iron War are given over to, respectively, the sociological and physiological elements of triathlon that help explain and frame the 1989 Ironman race. I didn't mind these chapters, but this wasn't the book at its most compelling.

One welcome segue from the stories of these two men was the historic confluence that led to this Gladwell/Outlier Moment: Why did so many superb individuals show up in one place, at one time, when the pool of athletes participating in triathlon was so small? That one is still a mystery, and we debate it on internet forums today. But one reason why we struggle now, 20-plus years later, to pull out of athletes the performances turned in by those racing a generation ago, might have to do with what triathlon represented in the late-70s and early-80s that attracted men like Scott and Allen.

This book is criticized by its two protagonists, who take umbrage to Iron War's literary device: the very personality traits that attracted triathlon's early adopters were coins which said "genius" on one side, and on the other said— well—read the book and you'll see what was on that coin's other side.

I love good stories. For this reason I prefer fiction. Accordingly, and as a rule, I don't much care for books on triathlon. But Iron War is a crackling good story, even if I already know the ending—even though I saw the ending (I was in that vast-but-silent entourage behind Mark and Dave as the clock approached 3 pm).

Mark and Dave maintain that the book reads like fiction because it is fiction. Much of what Fitzgerald recounted never happened, they say, or the events that spawned that moment were misinterpreted or mischaracterized. I knew this before I cracked the cover. Many times I came to a point when I said to myself, "How could Fitzgerald know that! He's making that up!" I went to the notes at the book's terminus and, doggone it, there was always a citation. There are right about 1000 citations, roughly 4 per page.

I was one of triathlon's early adopters. I took part in Mark Allen's second-ever triathlon, and by 1981 had completed as many Ironman races as Dave Scott had. I suspect many of us who were in triathlon's vanguard have personalities that sit somewhere along the psychological gradient. So what? If my moments of inspiration are had only in my manic moments—if my warts and flaws are a necessary companion that allow me my triumphs—I decry my faults at my own peril. I carry these flaws, these scars, these failures, these moments of self-loathing, these periods of sorrow and depression, in a sort of mental hope chest. My most precious moments are only precious because of the presence of my worse angels.

I've always been a fan of Dave Scott and Mark Allen. But they've always been two-dimensional to me. Life-sized cardboard cut-outs. I must tell you I love them both more now, after having read the book. The book has added that third dimension, and their darker angels provide me a permission slip to rise and fall, ebb and flow, fail and succeed, just as they did.

Iron War is the very first time our sport has engaged in Krakauer-style journalism, where full-featured personalities are presented to readers without excuse, or pause, or an author's self-censorship. Iron War is Fitzgerald's Krakauer moment. He may not quite yet be a craftsman on par with Krakauer, or Michael Lewis—he inartfully employed every known English synonym to up-chucking except technicolor yawn—but he's on his way. Bravo, Matt.

Dave and Mark have filed suit against this book's publisher, citing "inaccurate and defamatory assertions." There is no question about the thesis that drives the narrative: Their traits and experiences at once bedevil and propel each man toward, variously, difficulty and greatness. Fitzgerald would not be the first to create a straw thesis in order to move a story forward. Whether that has happened in Iron War and, if so, to what degree, I can't know.

To those of my fellow early adopters who take issue with the idea that our demons were the ants in our pants that drove us, you have short memories. It's not that we weren't balanced. All our extreme behavior leveraged on one side required a robust weight on the other side. Triathlon—at least back in the early days—provided us just that counterbalance.

What Iron War does not do is present Dave and Mark as crazies. Rather, they were among the sanest in that early group and the book doesn't betray that. What I find amazing is that Mark and Dave overcame the handicap of sanity to become the superb performers they were.

Iron War: Dave Scott, Mark Allen, & the Greatest Race Ever Run is available hardbound, published by VeloPress, and is 336 pages with plenty of photography from triathlon's early days.

[Photo: The photo accompanying this article is the iconic one memorializing that race. It was taken by Lois Schwartz, and graces the cover of Iron War.]