Optimized to Train

Most of us triathletes tend to view bicycles as filling a few very common roles in our lives:

1) As transportation (akin to our cars, or walking). We’ve got to get from point A to point B.

2) As race equipment (akin to our running shoes, goggles, or apparel). It’s gotta be fast, light, aero, minimal.

3) As a fun sporting hobby (akin to our old tennis racquets and skis in the garage). Just going for a fun Sunday stroll.

I’d like to present an alternative view: Bicycles purely as a fitness tool, for training humans to become better and faster at the sport of triathlon. This looks at the bike in the same light as, say, a piece of Cybex or Nautilus gym equipment. The priorities here are different, as will be discussed. The key premise here is that – at least when viewed in this specific manner – many of the latest pieces of equipment do not fit the bill. They may be great at the first three jobs, but could use some work at the fourth.

In looking at the bicycle as a training tool, there is a single attribute that trumps all: Versatility. I want options. I want options with my tire choice, so I can ride any day my training dictates – whether rain, shine, ice, or dirt. I want options with my hydration, specifically bottle mounting options (and lots of ‘em). I want options for where I store my food on my bike or body. I want options for easily mounting a wide variety of front and rear lights for safety. The list goes on, but the point remains – any compromises in these key areas means a compromise in the ability to train.

In general we can assume that any consideration of weight, aerodynamics, rolling resistance, etc – are all out the window. At least when we look at these things as a goal in-and-of themselves. For example, I would not suggest that a triathlete ride their bike in an artificially high handlebar position to increase air resistance and better “train” themselves… if they would otherwise ride and race in a lower position. Biomechanical efficiency or “correctness for you” is more important in the grand scheme. However, I may suggest that someone train with heavy and/or slow rolling tires. They’re likely more resistant to punctures – which in the long run means more ride time and less time changing flats. As well, when you put your race wheels, tires, and tubes on the bike, you will notice a real improvement.

Herein, I’ll explore a few key areas which I think are important and oft overlooked. I challenge you to consider these, and think of other areas to address in order to more effectively train ourselves as humans choosing to perform this specific activity of triathlon.

Death of the second bottle cage

Around the turn of the millennium, a very curious thing happened: our frames started to lose their second bottle cages. Hmm… I always liked being able to have one bottle of water and one bottle of sports drink. It always made sense to me. As well, I like being able to ride longer than an hour or two without stopping to fill up. I could put a bottle in my rear jersey pocket, but then where do I put my arm warmers, vest, keys, cell phone, and food? I just lost a third of that real estate. I could mount an aero bottle system between my aerobars, but then I lose a place for my computer mount (because the new-fangled integrated stem that came with my aero bike doesn’t have room to mount the computer display). Wait a minute – there is a vast array of saddle-mounted bottle cage systems that I can use – great! Oh wait, then I have a much increased chance of ‘launching’ a bottle and having to stop to pick it up. Also, since I don’t have the flexibility of a Cirque du Soleil acrobat, I can no longer do a flying mount out of T1 during the race – the bottles are in my way.

Is my Scrooge-like attitude getting through? Ahem… WHERE HAVE ALL THE BOTTLE CAGES GONE? Aero frames are great, but staying hydrated and fed are better. And – if you ask my humble opinion – will have much more influence on the success of your training day. The Trek Speed Concept (pictured) is one of the remaining modern frames that features two standard bottle mounts, along with the Scott Plasma 3 and very few others. Wind tunnel data has consistently shown that there is often little-to-no penalty to having a bottle or two on the frame. And… does it really matter? Our sport is triathlon, folks, which involves running after cycling. What works well for a 40k cycling time trial does not always apply to an Olympic-distance triathlon, let alone longer endeavors. I want my cages back. Both of them. Pretty please?

Death of the Triple Chainring

In very recent years, we’ve seen the bicycle industry attempting to quickly and efficiently kill the triple chainring crankset. This movement confuses the heck out of me. What’s the huge, enormous disadvantage of a triple, say you? Weight! “Who can stand to carry around a whole extra chainring?”, says the devil on your right shoulder. The angel on the left replies, “Does that matter when you don’t physically have enough gear ratio to ride up the mountain without it?” Those who ride in mountainous terrain will tell you for certain that it’s better to have enough gear ratio at your disposal than saving 40 grams.

One can argue that there are some new two-chainring systems on the market which offer a comparable gear range to a triple, by combining your choice of front chainrings with a wide-range 11-32 cassette. I think these systems are great – as race specific equipment. You pick your chainrings based on course profile, and you’ve got a fantastic, fast-shifting, lightweight set up. However, for training, I argue that it doesn’t compete with the triple’s versatility. No double chainring system on the market can match the wide gear range of a triple. You either lose ‘uphill’ gear or ‘downhill’ gear, but you can’t have both.

For example, pick a 53/39 crank and 11-32 wide range cassette (Note: I understand that this is excessive for many, but bear with me, and understand that not everyone is as lean, fit, and handsome as you. It’s okay, we know how fast you are.) You’ve got all of the top-end of the 53/11 ratio, but your 39/32 low gear does not match the triple’s 30 tooth granny ring and either a 27 or 28 tooth cassette cog. If you want that low range on the double chainring setup, you must pick the compact 50/34. But then you’ve lost your top-end for going down the hill. Of course you can coast down the hill, but what if you so happen to be in the middle of a 5 minute interval that is supposed to be in X heart rate range? I want my equipment to give me every chance to complete my training as-intended, i.e. continue to pedal down the hill. Proponents of the double systems also argue that they’re better because they eliminate multiples of the same gear. For example, on a triple you might have the same gear three times with ratios like: Small ring/small cog, middle ring/middle cog, and big ring/big cog. I say – So what? Does it really matter? I personally think not, and we should all go ride our bikes more instead of worrying about it.

As well, the wide-range rear cassettes can present a problem for those of us who may ride on an indoor trainer from time to time. Those folks who live in large metropolitan areas may do 80% or more of their training indoors. A wide 11-32 (or more) cassette means you’ve got very large “jumps” (changes in gear ratio) between cogs. If your ride calls for X heart rate combined with Y pedaling cadence, you may not have the gear ratio that allows you to do the workout, period. A triple ring drivetrain lets you run a tighter ratio cassette while retaining excellent total gearing by virtue of the extra ring up front. If you have a double ring system, you can always swap out cassettes for riding indoors – assuming you have the tools, knowledge, and time to do so. Personally, I’d rather ride, sleep, or do just about anything else after work on a Monday night.

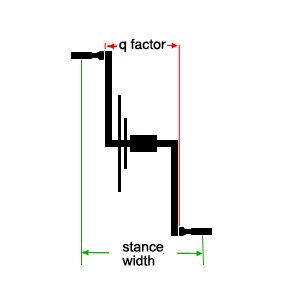

Some detractors-of-the-triple also argue that they’re “worse” because of the wider Q-factor, or Stance Width (effectively, how far apart your feet are on the bicycle). I believe that the importance of this topic is both over-inflated, and also flawed in the blanket assumption that ‘narrow is better for everyone’. Various studies have shown a variety of results on the topic. The thing that many newer triathletes are missing, however, is that the term Q-factor comes from actual Q angle of our knees. Generally speaking, wider hips mean a greater Q angle (this means you, ladies). Even for men, there are varying measures of hip width and Q angle. Perhaps narrower Stance Width tends to be more efficient, but that could also assume riders who so happen to be built well for cycling, or who are very biomechanically functional in general. Sit at a desk all day? Have a traumatic injury years ago? Lack general range of motion? Any number of factors can influence what width is best for you, so I say this: Don’t just assume that narrow is better. Wider could very well be better for you, and you don’t know until you try it out. In all likelihood, our wonderfully-adaptable human body won’t notice a difference (most triple cranks only add about 5mm of width per-pedal). I personally prefer a wider stance. It’s simply more comfortable, and I can more consistently hold a given wattage. Go figure.

I must reiterate that the double systems are not inherently bad. They have their purpose. If you’re racing the Mt Washington hill climb, for example, you absolutely want one of the new double-ring systems. This notoriously challenging race is only 7.6 miles, but summits the highest peak in the eastern US. It has grades up to – no kidding – 22 percent. On this type of course, you want crazy-low gears AND light weight. Saddle up with SRAM Red (with the mid-cage rear derailleur option and 50/34 crank) and the XX 11-32 mountain bike cassette. Or, for truly low gear, you can use an XX rear derailleur and 11-36 cassette.

Even for training, a triple likely isn't for everyone. If you're fit and live in a flat area like Florida or the Midwest, you likely don’t need all that gear (but it won't hurt you by any means). A 53/39 crank and 11-25 cassette might cover all your bases. Keep in mind, however, that the races you travel to may not be so flat – so having an alternate cassette option (i.e. 11-28) is a good idea. For those in northern California, Colorado, or any mountainous area, a triple could be just what you need. For many, the new “mid compact” 52/36 double is a great middle ground that perfectly fills the void between 53/39 and 50/34 chainrings. The point here is to get you to consider that there are options out there, and that the latest and greatest innovation isn’t always great – for you and your specific purposes.

If you do want to use a triple on your triathlon bike, your choice is largely between Shimano and Campagnolo. They appear steadfast in their support of the triple, and wisely so. Shimano used to offer triple chainring components up to Dura Ace level, but now the highest you can get is Ultegra (undoubtedly due to a decline in sales as triples have slowly dropped out of fashion). For the past few years, Campagnolo offered only a mid-low end Triple Comp group set, with no bar-end shifter option. For 2012, however, they introduced a new range of triple equipment, including the 3×11 Athena groupset. It appears that this is compatible with their 11-speed bar-end shifter set. FSA has a few triple crank options, but SRAM offers no road triples at all. The thing you can’t have yet is an electronic-shifting triple groupset, or a road triple power-measuring crank. You can, however, use a triple crank with a Cycleops Powertap rear hub without issue.

The versatility of a triple crank set also applies to Xterra athletes, who will see a huge variety of terrain. Currently, both Shimano and SRAM/Truvativ still offer triple cranks for your mountain bike, as do most other aftermarket manufacturers (i.e. FSA, E13, Race Face, etc). You should note, however, that mountain triple options are slowly dwindling with the advent of some new double chainring systems.

Limited tire clearance

While not universal, many modern triathlon bikes have limited tire clearance. Those rear wheel frame cutouts, hidden brakes, and aerodynamic wings sure look great, but they also tend to limit us to a 23mm tire. This isn’t necessarily the worst thing in the world, but again – this article is about options, versatility, and having equipment that allows us to train better, safer, and more consistently. It sure doesn’t hurt to use 25mm tires for training. You can use less air pressure, have better grip, and you may as well pick a tire that’s heavier and rolls slow too. It’s a training tool, remember? Just like runners lace up their lightweight flats for the race, I want my bike to actually feel and perform better when I set it up for racing.

My personal tri bike happens to be a custom frame with clearance for up-to-28mm tires. You read correctly: 28mm. What’s not to love about that? I use the bike to ride on dirt roads or paths that avoid heavy-traffic areas in town (and I’m sure your spouses wouldn’t mind you doing so as well). If I hit an unexpected crack in the road while taking a drink, there is less chance that I will crash; I’ve got more tire underneath me. In my fantasy world, bike manufacturers will combine a triathlon bike and cyclocross bike for the ultimate training tool. Triathlon geometry, mechanical disc brakes (i.e. Avid BB7 Road – which will work with TT-style levers), fender mounts, two bottle cages, a round seat post, and clearance for 35c tires. Slap on a set of studded tires for winter, and you can train regardless of weather or geography. Why the heck not? They can match the geometry to their normal “summer” tri bike, and we’re set. Strange? Yes. Geeky? Certainly. But – you cannot argue with its utility.

Wrap up

What’s this guy’s problem? Did he not get held as a child? Hey, take it easy. My parents held me plenty, and I hope this article can be read with the understanding that it was written somewhat tongue-in-cheek. What this all really comes down to is taking away excuses. If we really want to get faster, we need to face the music that it requires a lot of very methodical, very consistent training and recovery.

With this in mind, a good goal for our equipment is to get it out of the way. It should work all the time, on any day, and in as many possible conditions, situations, or terrain choices. Keep this in mind before that next purchase. Will it “cost” you anything previously mentioned? It may or may not, but we are all personally responsible for whatever we choose to do. Sometimes the newest thing isn’t the best – and sometimes it is. Take this as a prod from former 4th place Ironman Hawaii finisher, Mark Sisson, to “challenge the status quo by trying something old.”