Bottom Bracket How-To

Bottom Bracket How-To

In a continuing effort to educate our readers in all-things-bike, we offer another “How-To” article. The subject? Your ever-exciting bottom bracket. Well, I suppose they’re not that exciting, but I hope to at least offer an interesting inside look at how to properly install one. Even if you never intend to work on your own bottom bracket, it never hurts to see the process.

As with all How-To’s, the standard disclaimer applies – If you’re not a competent mechanic, take your bike to someone that is. Our advice is for entertainment purposes only, don’t try this at home, and only YOU can prevent forest fires.

The specific bottom bracket for today’s lesson is a Shimano Ultegra 6700. There’s no specific reason I picked this brand for the demo, other than it just happened to be what I was working with while the camera was handy. Most other modern threaded bottom brackets install with a nearly identical procedure, including SRAM, FSA, Race Face, and others.

Keep in mind that this type of bottom bracket is not used on every bike frame. No, bottom bracket standards seem to be multiplying by the minute. The good news is – the standard English-threaded (or “BSA”) bottom bracket continues to be the most common. The other two main types are BB30 and BB86, both of which require the use of a press-fit style installation (they do not thread in). In my opinion, BSA is still the smartest solution, providing a durable system that installs with very simple and inexpensive tools.

To begin, we need to go over the list of required equipment. It includes:

1. Bottom bracket – Ultegra 6700 in my case

2. Bottom bracket wrench (most of these are cross-compatible with the “Shimano standard”). I have the Shimano-made tool, but others are available from companies like Park Tool and Pedro’s

3. Degreaser and/or automotive brake parts cleaner

4. Grease and/or anti-seize compound

5. Bike rag(s) – old cotton t-shirts work great

6. Teflon plumber’s tape and surgical gloves (optional)

The first step is to be sure that your frame’s bottom bracket shell is completely clean. Use your degreaser and rag for this. If the BB shell is really nasty, brake parts cleaner can help break things up and leave everything like-new.

You may be thinking that it’s time to apply grease and thread the bottom bracket in.

WAIT!

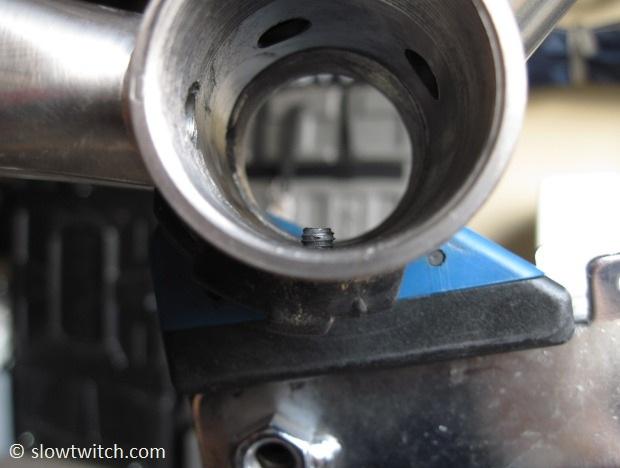

There is a common missed step to check first. This is one that seasoned mechanics are aware of, but the novice misses every time. Look in to that BB shell:

Notice anything? Say, a big bolt sticking in to the shell? It’s from the cable guide under the bottom bracket – assuming your bike has this (some bikes with alternate cable routing do not have one).

Sometimes this bolt is slightly too long, and interferes with the bottom bracket when you try to thread it in. To avoid trouble, simply unthread the bolt by a few turns (or buy a shorter bolt). They usually accept a 2.5mm or 3mm allen wrench, or occasionally a Phillips head screwdriver.

Now it’s time to apply grease to the threads of the BB shell. In my case, I have to use anti-seize compound instead of grease. How come? I have a titanium frame, which would cause dissimilar metal corrosion with the aluminum bottom bracket cups if used with standard grease. I don’t want seized bottom bracket cups, and this is a quick solution to ensure a happy frame. Steel, aluminum, and carbon frames (which have threaded aluminum inserts) can all live with grease.

Now, just spread it all around. I always wear surgical gloves for this procedure, as anti-seize is some nasty stuff. Be sure to wipe a thin layer on the outside faces of the BB shell, too.

Next, I put a little bit of anti-seize on the bottom bracket threads, and start threading in the drive-side cup (right side/drivetrain side of the bike). Keep in mind that most frames today feature English threading – meaning that the drive side has reversed, or left-hand threading. Lefty-tighty.

For now, I thread it in about half way. Next, grab the left side, or non-drive-side cup. Note how Shimano applies their own thread prep to each BB cup. Not all brands do this. Depending on manufacturing methods or how clean the threads are in your frame, you may have a loose interface with your bottom bracket’s threads. If that is the case, I’ll apply a few wraps of Teflon plumber’s tape to the BB threads – this simply helps to take up space between the male and female sides, and helps to prevent the bottom bracket from loosening over time. My frame and BB combination did not require Teflon tape.

Next, I thread in the left cup about half way. The non-drive side (left side) cup has standard right-hand threads (righty-tighty).

With both cups threaded in about half way, it’s time to tighten down the drive side (right side) all the way. With most brands of threaded outboard bearing bottom brackets, the torque specification is in the neighborhood of 35-50 newton meters. If you’re like me and have installed a million of these things, you know what that feels like and don’t bother with the torque wrench (it’s “One Grunt” on the farmer’s torque wrench scale – tight, but not TIGHT). If you’re doing this for the first time, however – it would behoove you to purchase a BB socket tool for a 3/8” or ½” drive torque wrench. Always better to be safe.

After the drive-side cup is snug, I repeat the procedure with the non-drive-side cup.

Now, since you’re a responsible and thorough mechanic, you obviously remembered to wipe off the excess grease and/or anti-seize from the frame…

You’re done, right? WAIT! If you loosened up that bottom bracket cable guide bolt… don’t forget to thread it back in.

NOW you’re finished.

Later, I’ll cover the specifics of how to install the corresponding crankset for this bottom bracket.

Nit-Picky Mechanic’s Note:

This installation assumed that your frame’s BB shell has already been prepped. This is also called “chasing and facing” a bottom bracket shell. You see, most bike frames are painted. Paint tends to get over-sprayed on to the faces of the bottom bracket shell, and in to the threads. This is bad. It ends up causing the bottom bracket cups to sit non-parallel – or for the BB shell to be effectively too wide. Either condition causes bottom bracket bearings to die an earlier death than they should. A road BB shell is supposed to be 68.0mm wide, and have parallel faces… not 68.5 with non-parallel faces.

The “chasing and facing” procedure re-cuts the threads, and cleans the excess paint off of the faces of the BB shell. It works great. The only problem is that it requires time, and a set of tools that cost several hundred dollars. Time and cost that almost zero bike manufacturers are willing to spend (so you have to do it yourself, or pay a shop to do it).

Thankfully, my titanium frame has no paint and did not require this to be done. But for every painted bike I’ve owned, I’ve always made a point to disassemble the cranks and bottom bracket, and go through with this procedure before ever riding the bike. I simply can’t cover it in this How-To because that tool set remains as one of the very few bicycle tools I don’t personally own.

Start the discussion at forum.slowtwitch.com