The Moki Martin story

The mission was so highly classified that the world didn’t know about Operation Thunderhead until 36 years after Moki Martin and a small group of SEAL teams set out for the North Vietnam coast on June 3, 1972.

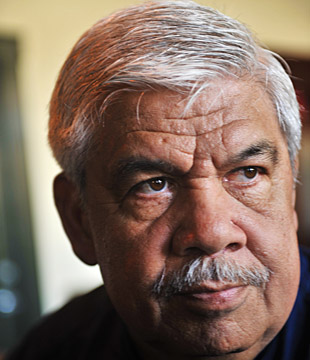

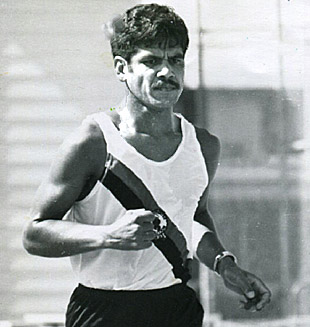

His military ID read “Philip L. Martin,” but his SEAL team and all his friends knew him as Moki, a nickname given to him when he was a skinny kid in Maui. He was an accomplished free diver, swimmer and surfer with a taste for adventure that led him to the Navy — and eventually to play a significant role in the early days of triathlon.

The mission was to rescue American prisoners of war attempting to escape a North Vietnamese prison in Hanoi. The initial thrust called for several four-man SEAL teams to embark in darkness in mini-subs to a small island 4,000 yards offshore to await a rendezvous with the escapees. Warrant Officer Martin and Lt. Dry, members of an Underwater Demolition Team element of the SEALs, led one of the teams that embarked from the submarine USS Grayback.

Their 20-foot-long Swimmer Delivery Vehicle (SDV) fought strong surface and tidal currents, and ran out of battery power which left them unable to reach shore or return to the Grayback. Dry and Martin and the rest of their team swam the SDV out to sea to prevent it from falling in enemy hands. When a Navy rescue helicopter arrived 7 hours later, they sank the damaged SDV and were ferried to the cruiser Long Beach.

Immediately, Martin and his team decided to return to the Grayback to warn the other SEAL teams about the currents.

On the night of June 5, 1972, the helicopter bearing Martin and his team spotted a signal at sea, but it turned out to be a distress signal from another four-man SEAL team. The Grayback had aborted the planned drop because of enemy patrol boats in the area, but the message didn’t reach the Long Beach in time. Worse, visibility was poor and made altitude reading difficult.

When the pilot signaled for the team to exit, Lt. Dry was the first to jump and was killed instantly when he hit the water from high altitude. Martin survived the massive impact, although his knee was badly twisted and he was only partly conscious. Two other UDT team members were also injured, one severely.

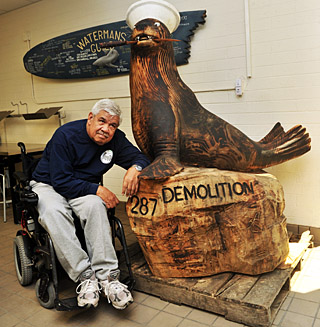

Three decades later the mission was declassified and Martin was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps Commendation Medal with a combat “V” for valor. Specifically, Martin was cited for valor for his part in the rescue of his two injured SEAL team members and for the preserving the body of Lt. Dry until recovery.

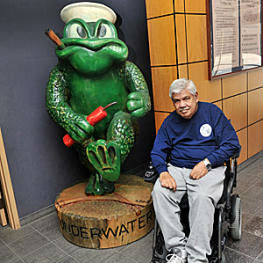

At a March 18, 2008 medal ceremony in Coronado, Martin said, "I accept this award on behalf of all of you from Alpha Platoon… This award is for all of you."

Moki Martin received his medal in a wheelchair, a quadriplegic. In an irony amplified by his extensive wartime service under fire, Martin’s injuries were suffered on a bicycle training ride along Coronado’s shoreline at 6:30 one morning in October of 1982. That ride was a part and parcel of his embrace of the new sport of triathlon soon after he returned to Coronado in January 1975 as a SEAL instructor.

From 1975 to his accident in 1982, Martin was at ground zero of the birth of the sport of triathlon In San Diego. While not a super athlete, he exemplified the contributions, influence and varied roles that Navy personnel such as Cmdr. John Collins and his wife Judy played in triathlon’s foundation. While enjoying participation in early races such as the Horny Toad Triathlon and Optimists Coronado Triathlon near SEAL training headquarters, perhaps his biggest mark was made founding the half Ironman distance SUPERFROG Triathlon in 1979 – one of the longest continuously running events in the sport’s history.

Underscoring his indomitable spirit, Martin remains active supporting current race director Mitch Hall in the Superfrog and SUPERSEAL triathlons at the Naval Amphibious Base in Coronado. After his discharge from active duty in May 1983, Martin remained an active member of the Naval Special Warfare community, giving lectures on “Lessons Learned in Vietnam” to Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL students. He also gives lectures to schools on disabilities, the SEALs and triathlons.

Slowtwitch: Where did you grow up?

Moki Martin: I grew in the ‘50s in Paia, a beach town on the north shore of Maui. I spent a lot of time on the beach surfing and did a lot of free diving. Which led to my interest in the Navy and to become a Navy frogman and later on a SEAL.

ST: Did you play any team sports?

Moki: None whatsoever. I was so small. I joined the Navy right after graduation from Maui High School and I weighed 120 pounds and stood maybe 5 foot 9. Over the next few years, I put on three inches and maybe 50 pounds. I signed up in Maui and immediately flew on to San Diego for boot camp. I spent two years on the USS Orleck where I ran the steam engines. During that time I moved up in rank to second class petty officer and I kept putting in my request to go to UDT (Underwater Demolition Team) training, which was very exclusive. At the time they limited UDT membership to 100 and only replaced the men who quit or retired.

ST: That was before Vietnam?

Moki: That all changed when Vietnam started up. Some folks in Washington believed that special operations troops were crucial instruments in modern warfare. So they formed two SEAL teams from UDT teams, one on each coast, and they drained the UDT teams dry.

ST: 50 years later, SEALS have become a crucial instrument of U.S. military force.

Moki: I think the military has gotten a lot smarter. The big conventional troops are necessary but expensive to maintain and to support. Now the guy in charge of Special Operations Command is a SEAL who was one of my students – four-star Admiral Bill McCraven.

ST: When the Vietnam began, how did your life change?

Moki: I got orders to go to UDT training in the last part of ’64. I went there three months early to get ready. I always stayed in shape swimming. But I could not run. One of my UDT instructors told me if I ran any faster I’d be walking backwards. So I took that to heart. Of the 130 guys who started in Class 35, I was one of 36 who graduated.

ST: How did you make the grade in running?

Moki: Teamwork. Everything you did was with six-man boat crews. I learned to run with my crew. I relied on them and they relied on me and I loved that. We did a four mile run every week and you had to go faster in each phase. To get into the final phase you had to go below 30 minutes. That was scary. Seven-thirty miles. In boots. On the beach.

ST: How could you help the others in return?

Moki: Because I was a petty officer, I was a leader. I was always the senior guy. I was a strong Hawaiian paddler – so I was always in the number one position – the stroke guy.

ST: How did you cope with cold water endurance tests?

Moki: Cold water was a great motivator. Get out quick, warm up. I had an advantage. In 1957 my brother-in-law bought me some revolutionary new swim fins called Duck Feet and I’d been using them for years before UDT training started. Plus I knew how to swim in the ocean, I knew how to ride the chop. So I was really fast. The instructors quickly figured that out — ‘Moki is pretty fast, so let’s put him with a guy who is about 10th on the list.’ Soon I was dragging this guy, making him swim faster.

ST: What got you through UDT training?

Moki: The key to my success, was based on Maui. I could swim. I could handle the open water. Beyond my swimming ability, working on a team made me better. When they put you together under intense pressures, you form bonds which last forever. With the guys in my class, I achieved goals I never thought were possible.

ST: You started UDT training in September of ’65 and were in Vietnam a short time later. When did you and your UDT team members become SEALs?

Moki: Once we were exposed to combat, we observed some of the SEALs and advisers and saw what they were doing. Eventually I was sent to do 8 weeks of training, mostly in land warfare and weapons. When I got back, I went directly to a SEAL team.

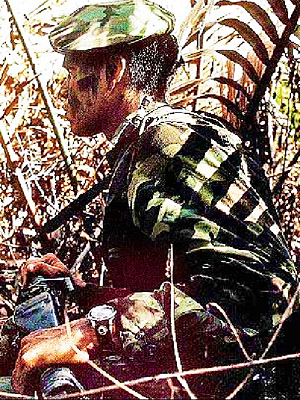

ST: What were your missions?

Moki: We worked a little above the Mekong Delta where the major rivers flow into Saigon. That is where the Viet Cong used to zero in on the ships. The SEALS were there to harass and interdict the enemy. We did a lot of ambush patrols. Capture the enemy. Interrogate him. That’s what I think we excelled at – gathering intelligence. Attacking the Vietcong infrastructure. Advising local forces.

ST: What did you think about Operation Thunderhead?

Moki: It was to be my last mission and it was something to look forward to. I had already made 5 tours. So now I was in a very complex, very sophisticated operation that involved a Navy submarine, Navy helicopters and search and rescue. This was a very sensitive Op. We were to land on the enemy beach and bring these guys back to the submarine – or to a point where the helicopters could pick them up.

ST: How did it turn out?

Moki: It didn’t quite go as planned. The weather was bad. One of our guys got killed on a helicopter insertion – the last SEAL to get killed in Vietnam. I was on that op and things just kind of snowballed. There are a lot of things in retrospect that might have been anticipated – ‘Hey, this current might be a little bit stronger than we thought.’ I think part of it was this: We are water guys. We know currents. We know from hydrographic charts how to land ships. But we didn’t quite have the clout to say no.

ST: This was your last SEAL mission. Where did you go from there?

Moki: I made warrant officer but SEAL teams didn’t have warrant officers. So I went back to the fleet for a couple of years. Broke my heart. In January 1975, I came back to Coronado as a BUDS instructor.

ST: The year of the first triathlon, September 25 in Mission Bay.

Moki: When I came back to Coronado, triathlon had not begun, but I was ready. I kept swimming and did a lot of running on the ship even when it was at sea.

ST: How did you get involved?

Moki: A SEAL buddy was in a group of runners in Balboa Park who called themselves the Horny Toads and I hooked up with them. We ran and did biathlons and early triathlons in Mission Bay and Coronado. One of those guys was a SEAL, John Dunbar. He called me up in ‘78 and said ‘Moki, you’re going to love this race.’ I said ‘Tell me about it.’ When he told me about the Iron Man, I thought ‘God, you got to be kidding!’

ST: Were you tempted?

Moki: No. I told John that a couple guys are interested in it and Tom Warren and Chuck Neumann did well at the 1979 and 1980 Iron Man. But it made me think. ‘Let’s cut the distances in half and make it little more palatable and put on our own race a month before Ironman.’ We called it SUPERFROG and I think I even coined the name half Ironman. In 1978, two guys tested it out. Then in 1979, we opened it up for the public and 19 guys showed up.

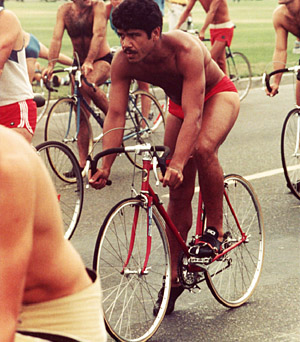

ST: How good a triathlete were you?

Moki: I might have been in the top 20 of some of those races. There were some awfully good guys, starting off with Tom Warren and Bill Phillips — I could never beat that guy. The other young guys starting off at the time included Scott Tinley and his brother Jeff and Chuck Neumann. All these guys placed in the top 10 at Iron Man in the early years.

ST: Your SUPERFROG was one of the first triathlons. But the Optimists Club Coronado Triathlon came first. What was that race like?

Moki: The Coronado Triathlon started out with a 4 mile bike, then a 400 yard swim and finished with a 1 mile beach run. The day before, they had a one mile swim and a 10k run and if you did those two and the triathlon that weekend they called it the Hard Rock. My biggest claim to fame is I was 2nd in the 1980 Hard Rock.

ST: Was it exciting to be part of a brand new sport?

Moki: Triathlon was a revolution – a new form of endurance racing. It encompassed the best of swimming and the best of cycling and showed how good are you when you’ve done those two sports and start the run. I thought that was neat. And it was great meeting the super athletes of the sport at the time – Tinley, Tom Warren, all those guys that to me were the foundation of the modern triathlon.

ST: What was your first SUPERFROG course like?

Moki: We started in front of the Hotel Del Coronado and you swam down the Coronado beaches to the Navy base where BUDS is located. Then we biked up in the hills around South Bay and finished in Imperial Beach. Then you ran up the strand back to Coronado.

ST: How did your race evolve?

Moki: After seven years, it had grown to 230 entrants and became unmanageable because you had many cyclists riding city streets and nobody controlled the intersections. So we put the race on the base. We had a lot of cooperation between the North Island and the Naval Special Warfare command. We tried not to interfere with base operations, so we held our races on Sunday.

ST: What sort of people competed?

Moki: Mostly SEALS and Marines. Lot of them were like Mitch [Hall, current SUPERFROG race director, a Navy SEAL], new to the sport. It might have been their first or second triathlon. We didn’t have any pros.

ST: Where is the course now?

Moki: Five years ago we decided to go completely off the base and run the races from more of a commercial point of view. With guidance from San Diego race director Rick Kozlowski, we created SUPERSEAL as an Olympic distance race and added it to the SUPERFROG. The fields grew fast. So then we split the SUPERFROG off to September and put the SUPERSEAL and a sprint event in late March.

ST: What have these races meant to the sport of triathlon?

Moki: To many, our causes are great. The prime beneficiary is the Navy SEAL Foundation, which helps wounded SEALs, their wives and children with education and counseling and stuff like that. We also benefit two local sports groups for the children. — The Islander Sports Foundation, which promotes sports for middle school and high school students, and the Coronado Optimists Club. So it’s not a total commercial venture-enterprise. Triathletes also like it because it’s held on the SEAL training ground. Also, SEAL basic training is a combination of various elements of triathlons. So it fits in with the SEALs style of training.

ST: How did you become paralyzed?

Moki: In October 1982 I went on my morning ride from Coronado to Imperial Beach. It would have been a 9 mile ride each way. It was 6:30 in the morning and it was October when the light is getting a little bit later in the day. The road made a slight turn to the right. I was going through my gears and I looked up and this guy was coming right at me. I thought ‘If I go to the right. I’ll end up in the ice plants and the sand.’

ST: That would not have been so bad.

Moki: No. But I thought, ‘Well I’ll just go out in the road and go around this guy.’ And then he made the same move. He claimed later he didn’t even see me. He was on the pedals looking at the ocean trying to look at the surf. He was a young surfer from Imperial Beach. He was on a bike also. Coming right at me. Going north in the southbound lane.

ST: What were your injuries?

Moki: I damaged my spinal cord at the C-5 level. I was an immediate quadriplegic.

ST: How long did you continue in the Navy?

Moki: Six months later the Navy retired me. Actually they didn’t retire me. I’m what they call Active Retired. I give lectures at the Naval Special Warfare Center to all the junior officers on my lessons learned. I do what I can. I also give lectures to schools on disabilities, and the SEALS and triathlons. I put on art shows.

ST: Art shows?

Moki: I have a Bachelors degree in Arts and Letters from San Diego State. Go figure. Mostly painting and drawing. Much of it is Hawaiian heritage, Hawaiian themes.

ST: You have been married through all this?

Moki: Cindy is my wife and we’ve been married for 44 years. She carried me through the Vietnam War and especially through my injuries. I call her my mentor and my BUDS instructor. She is always watching over me. She doesn’t have to say much. I know what she is thinking.

ST: And your children?

Moki: We have two children. Joel who is 40, is a professional photographer in Los Angeles. Callie is 24 and she is in a masters program for counseling.

ST: How proud are you of what you’ve done in triathlon?

Moki: Being Hawaiian – it’s natural for me to think ‘Let’s party. Let’s have fun.’ I’ve always been the guy who wanted people to have fun and triathlon is a great way to do that. I think triathlon draws unusual types of people together. Triathletes all talk the same language. Especially today. They all have that very positive, very disciplined mind. They are mentally strong. I see a lot of those traits in my SEAL teammates. Same kind of ethos. I think triathletes are like that. They all have their personal reasons for doing triathlon. Always challenging themselves. Not everybody is going to be Chris McCormack or Michellie Jones. But everyone can have their own challenges and their own goals. I just want them to have fun taking the challenge and doing the race.

For information about the September 29 SUPERFROG Triathlon: www.superfrogtriathlon.com

Start the discussion at forum.slowtwitch.com