Up close with Allen Lim

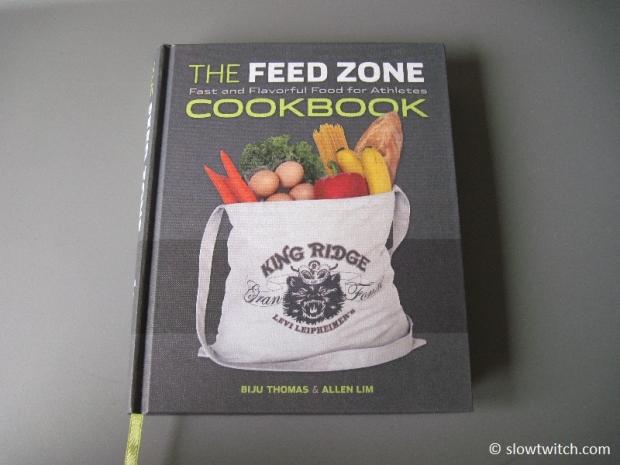

Dr. Allen Lim is a physiologist, sports scientist, coach, nutritionist, and all-around endurance sports smart-guy. Lim is known for his work with professional cycling teams, his cookbook, and his company, Skratch Labs. We covered his general philosophy the making of his famous sushi rice cakes HERE.

I had the opportunity of interviewing Lim twice in August of 2012. First, over the phone on Friday, August 24th, and next on the early morning of Saturday, August 25th, as he was preparing food for the riders of the USA Pro Cycling Challenge. The text that follows below is an aggregate of those two conversations.

As a journalist, I appreciated Lim’s candid responses and quick follow-up – clearly this guy is passionate about his business, and has worked hard to make it grow so quickly. As an interested triathlete, it was the opportunity of a lifetime to ask questions for my own selfish desires. I, like untold numbers of our readers, have struggled mightily to figure out a nutrition plan that achieves the magic trio of sufficient fueling/hydration, no GI distress, and good taste.

Below, I’ll write the biggest ‘take-homes’ that I got from our conversations (some of which was spoken with the voice recorder off), and what I think may answer some of the most common questions of our readers. Of course, the standard disclaimers apply: I’m not a doctor, and I don’t play one on T.V…. be willing to test for yourself, and always wear proper eye protection. And – if you don’t want to listen to me blab, just skip to the interview part to hear it from the real expert.

1. Rely on simple, real food whenever possible. The shorter the ingredient list and shelf life, the better.

2. Race with the same foods and drinks that you train with. No eleventh-hour changes to the latest-and-greatest nutrition product (even to Lim’s own products).

3. Carbohydrate is the primary fuel needed for exercise. Protein and fat (such as bacon and eggs in his rice cakes) are there for taste. The X factor in triathlon is running – some people have difficulty dealing with the protein and fat on-the-run (but tolerance is highly individual based on ancestry and cultural adaptation).

4. The nature of long-distance triathlon racing forces a sub-optimal fueling plan upon the athlete. Even if it is not possible to follow a perfect plan, it doe goes a long way to optimize what you can – i.e. carrying what you can with you on the bike, using a ‘special needs’ bag, etc.

Editor’s note: The food that Dr. Lim is referring to towards the end of the interview is covered in the original photo gallery piece. The host hotel for that particular stage of the USA Pro Cycling Challenge was tasked to provide rice, eggs, and bacon in large trays for Lim and Chef Biju Thomas to make in to rice cakes. However, as we detailed in the gallery, the rice was far too wet, had a poor texture, and was just plain bad. Lim then called an audible to use their own rice cookers for a last-minute save to make better quality, better-tasting rice cakes.

Slowtwitch: Please go through the highlights of what you do at Skratch Labs – the mission statement, so to speak.

Dr. Allen Lim: You have the ever present problem of stomach upset, bloating, and gut rot, which other sports drinks were creating for the athletes I was working with. We offer an all-natural sports drink that – for lack of a better term – isn’t a chemical shit show. When I was working with teams like Garmin, one of the more ubiquitous complaints I got was that the sports drink that they were using was making them feel sick, not agreeing with their stomach, or leaving too much flavor in their mouth; it was all they could taste. With Garmin, we were trying to find a product that was commercially available to solve that problem. But everyone is such an individual, it seemed impossible to find a product that worked for everyone.

At that point, I literally started making a drink mix from scratch… mixing and matching different concoctions – using both science and common sense to guide me through that process. And, more importantly, using the practical feedback from the athletes I was working with. And I think that was the key – listening to the athletes, listening to their stomachs, looking at their performance. That’s how Skratch was born.

For years, I couldn’t tell anybody, because we were sponsored by other companies. So I made this stuff in my kitchen, and we secretly replaced the other products with Skratch, and it got the nickname ‘Secret Drink Mix’. By the time I moved on to Radio Shack, we were still using the Secret Drink Mix, and other teams and athletes started asking for it. So we started making larger production runs, using a paint shaker from the local hardware store, and selling it to local pros and teams.

ST: Do you work with pro triathletes, or only cyclists?

Dr. Lim: My core is really in cycling. Our second largest population after cycling is actually Nascar. There are 6 Nascar teams who buy and use our product. I imagine there are a lot of triathletes who use the product. We had some athletes at the Olympics who we know buy and use our product who are triathletes. It’s hard to differentiate the people who buy our product in our online store, and know what sport they do. Flora Duffy used our product at the Olympics, Kristen Peterson – another pro triathlete – uses our product.

ST: What is your take on nutrition for long course triathlon racing – anything from a half Ironman to an Ironman or longer. You see people using a lot of highly concentrated gel and drink products simply to get the calories in. Is there any other way to realistically do it?

Dr. Lim: I think the whole issue of using a very highly concentrated solution… is just completely wrong. It’s the biggest mistake that a lot of triathletes make. But – I don’t think it’s a mistake they necessarily want to make; I think it’s a mistake they have to make due to the nature of how these feed zones are set up, and the nature of the entire day. They’re trying to get the calories in to match their energy expenditure, but that’s only one half the equation.

You’ve got to get the calories in to offset your glycogen loss, but you also have to stay hydrated. It’s the same with how you can go weeks without food, but only a few days without water – I think the same is true for athletic performance. When you become dehydrated, your performance really drops off much more rapidly than a loss in fuel source. For the most part – and I hate to say this – but a lot of amateur athletes have plenty of fuel on board, and they’re not going that fast, so they really don’t need that many calories while they’re exercising. Energy expenditure is a greater problem only for the very, very elite. For the recreational amateurs who think they need these highly concentrated solutions and gels – they are actually creating more problems than they’re solving.

From what I’ve observed, many athletes never do this [high concentrated solution] protocol during training, but in racing they think it is magically the right thing to do, and they end up having Gastrointestinal distress. And, correct me if I’m wrong, but it almost seems like GI distress is an accepted consequence of being a triathlete. There’s almost this badge of honor for who has the worst stomach.

ST: I’ve seen you promote a mantra of to the effect of: ‘Drink your hydration and chew your calories’. What does this mean and why do you promote it?

Dr. Lim: That’s what I’ve found to work best in long endurance events, like the Tour de France or Giro d’Italia. We found that when you eat your food, and then you focus on having a lower calorie hydration solution that allows you replace all of the electrolytes that you lose in your sweat – primarily sodium – you end up doing a much better job at getting both your calories in and your hydration needs met without the Gastrointestinal distress and upset stomach. And the reason is that when you bypass normal digestion with a highly concentrated solution, the osmotic pressure that that suddenly creates in the small intestines is literally like trying to shove way too many cars on to a highway and getting in to a big traffic accident. At that point the whole entire highway closes and you can’t get any cars (or food) past.

It really comes down to an issue of osmosis. If you have a very highly concentrated solution in your gut that suddenly appears acutely, what your body does is actually draw fluid out of the body in to the small intestines to dilute it, so that it can actually be pulled back in to the body. Active transport of sugars and nutrients can only do so much. When you have something in a solution, such as a gel, or a 400-calorie electrolyte solution, you’re rushing things in suddenly and creating this acute load that the gut can’t handle. If you eat food, though, you go through this whole process of digestion in the stomach. You convert that food in to a bolus of chyme in the stomach, and then it trickles from the stomach in to the small intestines at a very paced interval.

In a sense, it’s almost like having a stoplight at the entrance of a highway that allows one or two cars to by every few seconds, rather than trying to get all of those cars on at the same time. What ends up happening with real food is you get a consistent source of calories that trickle in to your body throughout the whole entire event, rather than having these big shocks to the system. The ultimate irony is that people think they need these high carbohydrate solutions or these gels because they can’t digest, and they almost want something that is already broken down for them. But when they do that, all they’re doing is basically creating an oil spill inside their gut.

ST: Do you have any general ranges or guidelines for someone doing an Ironman and wanting to do a ‘real food’ plan? How many calories per hour or grams of carbohydrate are they looking at taking in?

Dr. Lim: You’re looking at replacing about half your energy expenditure per hour – for an event that lasts longer than about 3 hours. If it’s shorter than 3 hours, you’re likely to have enough glycogen on board that as long as you have a little bit of sugar coming in through your sports drink, you’re going to maintain your blood glucose. And maintenance of blood glucose is probably more important in terms of how somebody feels than whether or not they have the fuel to do the event. If it is longer than three hours, you’re going to be potentially running through your glycogen stores.

An average 70 kilo / 154 lb person is going to have 2,000 to 3,000 calories of glycogen on board, depending on whether they’ve been eating enough carbohydrate coming in to the event. But let’s just say they do have ample carbohydrate on board. The most elite individual probably won’t be burning more than 800 to 900 calories per hour. So at most, they might need 400 calories per hour, which is 100 grams of carbohydrate. If you’re finishing 3 or 4 hours after those top guys, your energy expenditure might be half that, so you may only need 50 grams of carbohydrate per hour.

If you think about the hydration needs, though, between the elite individual and amateur individual – if it’s very very hot, both individuals may be sweating the same amount, and losing the same amount of fluid. So the energy expenditure between an amateur and elite may be very wide, but the hydration discrepancy may not be very wide. So let’s say that you’re easily losing one liter of fluid per hour. In a race like Kona, it could be double that, but let’s just call it one liter per hour. Well, at one liter per hour, you can drink two bottles of Skratch, for a total of 40 grams of carbohydrate. At that point, you may only need to eat a little bit of solid food each hour to get you through an event. I think that people sometimes miscalculate how much energy they need.

ST: The only problem is aid stations – sometimes you just have to rely on the course nutrition, and you’re drinking whatever the race offers. You just can’t carry 10 bottles on your bike.

Dr. Lim: Absolutely, and as I mentioned earlier, when I see triathletes making this huge mistake – I get the sense it’s a sense that it’s a mistake they don’t want to make… it’s a mistake that’s forced upon them due to the way these aid stations are set up and what they can actually carry on the bicycle or on the run. I’ve had triathletes tell me in the past that they’ve carried our single sticks of Skratch with them on the bicycle or on the run. When they get to an aid station, they take the time to pour in their own Skratch into the bottles and fill them with water. Even if it costs them a little time to do that, it ends up saving their stomach and they can go faster overall. A lot of the products available at these events are filled with coloring agents, flavoring agents, and emulsifiers that aren’t doing any good. There also tends to be too much sugar and not enough sodium. Almost none of these drinks have enough sodium to meet the needs of the majority of individuals out there.

ST: What do the nutrition sponsors think about what you’re doing with these rice cakes that you’re making for races like today’s stage?

Dr. Lim: That’s like asking Clif bar or whoever what they think about making pasta for someone. It’s not like they’ll say, "No! Don’t eat that steak! Don’t have pasta! Eat our bars – you’re sponsored by our bars!" What we’re doing is akin to making someone a sandwich in the afternoon. It’s food; it’s part of their day. Certainly packaged food is going to be part of what they eat. Guys who are sponsored by Powerbar aren’t going to stop eating Powerbars, they’re just going to add what we do to the arsenal of what they have. The bottom line is adding some variety.

ST: With triathletes stuck in the “sub optimal” feeding situation of long course racing, would you still say it’s better for them to do what they can – start with the right stuff on their bike, and then pick up what they have to? Or start experimenting with real food like your rice cakes?

Dr. Lim: Absolutely. It’s time for that community to start re-thinking what they’re doing – rather than just accepting what the race organizers are giving them.

ST: What would you tell a triathlete to eat during a race? If they’re getting 40 or 60 grams of carbohydrate per hour from a drink mix, and they need another 20 or 40 grams – what else should they eat?

Dr. Lim: They should eat something real. They should have a sandwich. I don’t know, have a piece of pizza. Have a leftover burrito. Have some oatmeal and a burrito. You know? Eat whatever they would normally eat.

The nature of it is this: If you try to break everything down in to carbohydrate, protein, and fat – which is done – and let’s say you get the perfect ratio of it, and it ends up being some sort of ‘RoboCop fuel’ that you can squeeze out on to a plate (which you actually see happen in a lot of hospitals). Would you be proud to serve that at your dinner table in front of all your friends and family? If you’re not willing to eat it in that situation, why would you do it for your race? It just seems totally arcane to me that people totally don’t distinguish between nourishment and nutrition. Nutrition is like ‘this compound and that compound… and we’re so smart and we know exactly what the body needs’. I don’t know what the body needs. After years of doing this with elite athletes, everyone is different. Everyone is their own experiment. I can’t say, “Everyone needs this amount of protein”. Some guy might be able to handle more protein because that’s how they and their family normally eat, and it was just a cultural adaptation.

And this food we’re making today is a great example of the nutrition versus nourishment. It’s shit rice, and we’ve got shit food. It’s got the same nutritional quantity as anything we’ve ever made, but it’s not right. It sucks. And, for the most part, that’s how a lot of the sports bars are. They have all the right nutrition numbers, but they’ve got all this other junk in them, and it doesn’t taste right. It doesn’t satisfy the pallet, or there’s too much flavor, and it upsets someone’s stomach. For whatever reason, they’ve got all sorts of emulsifiers and coloring agents and preservatives that they need to make the product last longer, and end up fundamentally not not being part of the nutrition.

We’re really getting back to the old school with real food. We’ve found that certain foods work better than other foods. Simple foods. High glycemic index, and not a ton of fiber. You could even use something like oatmeal, if you let it dry out… it’ll work pretty well. With the rice cakes, we’re not adding protein for its performance enhancing effect, we’re adding protein for taste. Whether or not a person can tolerate it tends to be individual, but it’s also generally easier to digest when you’re cycling – versus something like running. Of course I think that our drink mix is the best thing on the market, but in terms of food, I think triathletes should just start experimenting and making their own food.

Start the discussion at forum.slowtwitch.com