Reynolds Aero 58 and 72

While I’ve ridden a lot of wheels, I had never ridden anything from Reynolds until this year. Rob Aguero, Reynolds’ Director of Sales and Marketing, and Paul Lew, Director of Technology and Innovation, reached out to us in April to arrange a long-term test of their new AERO line of wheels.

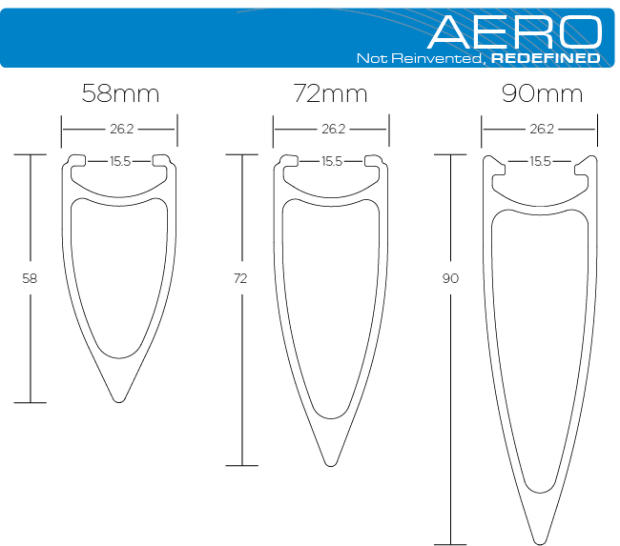

I’m familiar with Reynolds’ older v-shaped rims (32, 46, 66, 81mm), but Aguero told me that the AERO line is all-new and vastly different from previous product. We opted for the 58 front and 72 rear combination, seen here:

Let’s start off with the basic specs.

-MSRP $2,829

-1,670g/set (Rim-only weights: 575g front, 600g rear)

-16 front, 20 rear DT Aerolite spokes with internal 5.0mm hex nipples

-Rim width: 26.2mm at the braking surface

-Rim depth: 58mm front, 72mm rear

-Available with Shimano/SRAM 10/11-speed or Campagnolo 10/11-speed freehub

-Max tire pressure: 150psi

-No rider weight restriction

-Clincher only

-700c only

-Includes valve extenders, wheel bags, quick release skewers, Cryo blue brake pads, 11-speed freehub spacers, rim tape, and instruction manual

Out of the box, the wheels looked great. The graphics are striking, and are applied with a very unique process. According to Aguero,

“Reynolds has invested in a machine that [effectively] sprays on a very durable and light weight paint directly on the rim. Depending on the rim depth, this process can save up to 23 grams in comparison to the Mylar decals we have been using up to this point. The process is also lighter than heat or water transfer appliqués which typically require the rim to be painted and then clear coated (obviously adding weight).

The AERO wheels and the Element disc will be the first wheels to receive this process, but all Reynolds carbon road product for 2014 are planned to have the ‘inkjet’ graphics.”

Mechanically, the wheels look similar to many products on the market. Start with a minimal front hub and 16 straight pull bladed spokes (in this case, the excellent DT Aerolite):

The rear hub features 20 spokes and DT’s star ratchet drive mechanism. I opted for the SRAM/Shimano 9/10/11-speed freehub (a Campagnolo version is also available):

One note about that freehub – Reynolds has a unique solution to the modern spacer quandary. For the full detailed story on cassette spacers, click the link at the bottom of this page (Cassette How-To, Part 2). In order to use a 10-speed cassette on an 11-speed freehub, you need 1.8mm of spacers in addition to any other spacers that come with your cassette. Rather than supply a 1.8mm spacer for you, Reynolds gives you two of the standard 0.9mm 10-speed spacers to stack up (nobody can seem to agree if this spec is actually 0.9 or 1.0mm… but it’s close enough that it doesn’t matter in the real world).

How many spacers should YOU use for this wheel? Here is our guide, based on your cassette choice:

SRAM or Shimano 9-speed: 2 x Reynolds .9mm spacers

SRAM 10-speed: 2 x Reynolds .9mm spacers

Shimano 10-speed 2 x Reynolds .9mm spacers PLUS stock .9mm spacer (3 total)

SRAM or Shimano 11-speed: No spacers

The Reynolds AERO wheels have internal spoke nipples that require a 5.0mm hex socket. Reynolds says that internal nipples are a must on these wheels due to the sharp edge of the rim.

Also note the molded-in valve area:

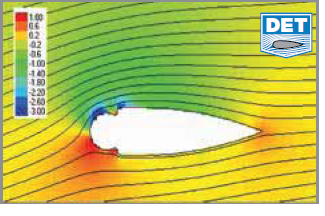

The biggest news with the Reynolds AERO line is a very unique rim shape, called DET. According to Reynolds,

“DET™ stands for Dispersive Effect Termination. It is a V-shaped rim design that smoothes turbulent, energized airflow and re-attaches it to the aerodynamic surface, effectively reducing aerodynamic drag. This new shape also provides significant improvement in handling. DET shifts the center of pressure further forward of the center of mass (or hub/axle center), which creates a more stable steering force. With DET™ the side force associated with a crosswind is constant over a wider range of crosswind angles. Translation: predictable steering with superb handling.”

The following image illustrates 31mph and 10 degrees yaw:

If there was one feature of the wheels that interested me, this was it. Put simply, it flies in the face of what almost every other wheel company is saying.

I’m looking at two key things here:

1. Overall rim shape. Reynolds states multiple times on their website that the AERO wheels have a V-shaped rim. However, while on the phone with Paul Lew, he was very clear with me that it is not a V-shaped rim. Huh?

Traditional V rims have flat sides and a rounded ID, and the AERO rims have rounded sides and a sharp ID (not to mention being much wider than traditional V rims). Perhaps I’ll call it ‘V-shape 2.0’. Just eyeballing it, the two similar competitors that come to mind are the 2013 Shimano C50/C75, and the Mavic CXR 60 – both have a relatively sharp rim ID, wide brake track, and angled sides.

2. The Reynolds explanation of crosswind stability. Zipp’s Firecrest and Hed’s SCT technology are based around a very wide and rounded rim ID, which has a radius that is roughly the same as a bicycle tire. Zipp says that this reduces vortex shedding, or the buffeting that you feel as attached airflow breaks free from the rim. Zipp also states that their design moves the wheels’ center of pressure further rearward, reducing steering torque and stabilizing the wheel. Reynolds explanation is the polar opposite, saying that their rim shape moves the center of pressure further forward, citing that the airflow in the back of the wheel is too turbulent to effectively do what the others advertise. It’s rare that two companies say that exact opposites achieve the same outcome, so I was interested to say the least.

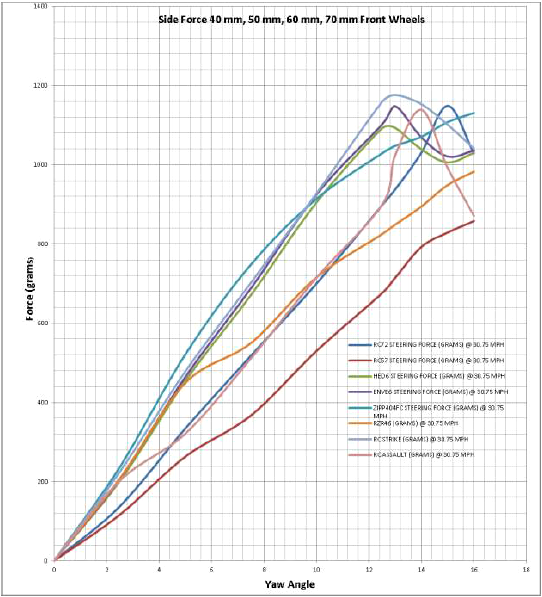

Reynolds does show several comparisons of side force in their white paper, which is available here:

http://www.reynoldscycling.com/downloads/DET%20White%20Paper%20Full%20Version-final.pdf

This is one such graph:

The text is too small to see very clearly, but we can tell you that – as would be expected from a manufacturer-generated chart – they show the best performing wheel to be their own, ahead of Zipp, Hed, and Enve. The test protocol was not made clear to me (e.g. brand/model/size of tire on each wheel, how measurement was done), so my jury is still out on the matter at this time.

The other unique feature of the Reynolds AERO 58 and 72 is a step-down that sits right at the corner of the braking surface. Reynolds calls it ISH, or Integrated Step Hook.

At first glance, I thought that this ledge was designed to trip the air into a boundary layer of turbulence, similar to other companies’ dimples or textures. Lew told me flat out that they do not believe in any features that are intended to create a boundary layer of turbulence on a wheel; that they simply do not work. Based on the Reynolds number at typical bicycle and wind speeds, he says that all of the air is already turbulent around the wheels and bike, so the boundary layer is useless. Instead, their goal is to reduce drag and turbulence by the rim shape itself. Their DET white paper states,

“It is accepted that flow transitions from laminar to turbulent at approximately Re = 500,000, less than half the value shown above. Thus, air flow associated with a spinning wheel at a velocity of 31 MPH is turbulent. This supports the concept that all air flow over a bicycle wheel is turbulent. This is an important concept. It suggests that energizing the boundary layer (the very thin layer of air on the surface of a bicycle rim or wheel) by the use of texture, dimples, or other means is ineffective and unnecessary because the boundary layer is, by nature of the dynamic motion of the spinning wheel, turbulent. In these turbulent flow conditions, some of the pressure force driving the flow creates eddies in the viscous (sticky) surface flow on the wheel. This aerodynamic characteristic results in the creation of a drag force. This drag force consumes watts (horsepower). Large local fluctuations in the airstream velocity occur close to the surface. The irregularity of the turbulent flow conditions results in significant energy loss. This accounts for the increased drag accompanying turbulent flow.”

When I inquired as to how the ISH ledge contributes to better performance, Lew responded in an email,

“It is common that small disturbances in airflow in localized regions can improve the overall aerodynamic performances. This is common particularly near leading edge contours and trailing edge re-attachment zones. This is the case for the ISH. Tire size varies depending upon rider selection and the tire shape is dynamic; it is always changing depending upon terrain, air pressure and tire design, and molded tire tolerances. The ISH helps to create a predictable airflow over the surface of the rim in a situation where the airflow would otherwise be unpredictable based upon the tire variability and environmental conditions.”

This explanation seemed good and well, but did not quite tell me what was actually the cause of the improved performance. The small relief area of the ISH could conceivably create a small vacuum – or a boundary turbulence ‘trip’ – but we’re not sure if this is what Lew suggests.

The ISH feature also has an interesting effect on rim width because it effectively thickens the braking surface. Similar to the Mavic CXR clinchers, the internal rim width is narrow relative to the outer rim width. Specifically, the Reynolds AERO wheels have an internal width of 15.5mm, and a measured outer width of 26.3mm:

One consequence of the ISH feature that I did not expect was that it nearly caused the wheels to be incompatible with my frame. When designing the bike, I wanted it to be compatible with 27 and 28mm tires. In order to accommodate this, the frame builder moves the brake mounting point a couple millimeters higher than ‘normal’ (e.g. away from the center of the dropouts), so that the top of the tire does not interfere with the brake. The only consequence is that you must adjust the pads towards the bottom of their adjustment range. On most wheels, this leaves my brake pads at about 80-90% of the maximum possible adjustment.

With the Reynolds AERO wheels, the last millimeter or so of braking surface is effectively missing because the ISH ‘ledge’ removes it. I had to drop the pads on my Dura Ace brake all the way to the bottom of the available range, and the pads just barely hit the rim properly. On most tri bikes designed for 23mm tires, this should not be an issue.

Only the 58 and 72mm rims feature ISH; the 90mm option curiously omits it:

The key point that Lew had for me regarding aerodynamics was an interesting one. According to him, the bicycle industry incorrectly uses the term ‘drag’. He says that it is actually lift over drag, and that this is the manner in which aircraft engineers speak.

Put another way, Lew stated that if a wheel’s drag is 100 grams, but the design also creates 25 grams of lift, the net result is 75 grams. He says that all other wheel brands are simply listing that net result as the drag – but not detailing what went in to creating the number.

Lew ended by telling us that he does not believe that the blunt-shaped competitors’ wheels are bad, per se – they’re just a different way to skin the cat. He called those rims “high drag, high lift”, and his design “low drag, low lift”. As an analogy to two popular triathlon frames, he stated that the older Specialized Shiv with super wide ‘nose cone’ is a high drag/high lift bike, and that the narrow Cervelo P3 and P4 are low drag/low lift bikes. He says that the two designs are valid, but that they work best under different sets of conditions – and that the low drag/low lift designs are easier to handle overall.

I’ll be honest – this explanation was so strikingly different than anything I’ve ever heard from a wheel or frame manufacturer that I had a difficult time writing clearly about it. I had a huge puzzle to piece together with information from emails, phone calls, white papers, blog posts, and advertisements. This wheel review was – by far – the most time consuming one I’ve ever done.

I suppose if I have one criticism of Reynolds, it has nothing to do with the product, but rather the brand and technology messaging. Each outlet seemed to tell the story a little bit differently, making it hard to understand what they were really trying to say. I pose the question to you, the reader: What do you think? If you’re an engineer, does their line of thinking make sense to you?

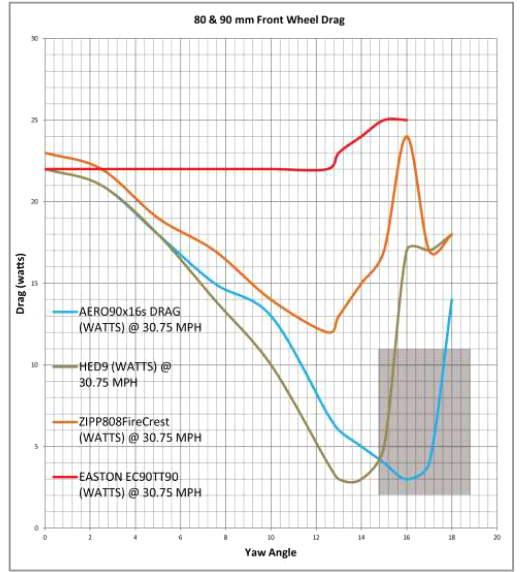

That aside, Reynolds did provide several graphs to me from their wind tunnel testing at the A2 facility in North Carolina. They claim a 3 minute, 6 second advantage over the Zipp 808 Firecrest, and a 6 minute, 54 second advantage over the Easton EC90 TT 90mm for an Ironman distance ride (assuming a constant 16 degrees of yaw):

Note that this test was for wheels only (e.g. no frame or rider was involved).

Reynolds tells me that the three clincher wheels (Reynolds, Hed, Zipp) used the 20mm Continental GP 4000 (non-S) that measured 21.0mm actual. The tubular-only Easton wheel was wrapped in the 22mm Continental Competition.

In my mind, this takes the Easton data out of the picture. Its tire was larger than the others, and it has been shown in many independent tests that the tread pattern of the GP4000 clincher carries an aerodynamic advantage of its own (the Competition does not have this tread pattern).

Installation and Riding

I opted to test these wheels with a pair of Specialized Turbo Pro 700×25 tires and S-Works butyl inner tubes. I chose the wider tires for their comfort, and I wanted to see how the width compared to the rim.

The first thing I noticed was that the tires installed really easily… as in – it was the loosest fitting tire/rim I’ve ever felt. I wondered if those tires happened to fit particularly loose, so I also threw on a 25mm Continental GP4000. It was a tiny bit tighter, but still a very loose fit.

While I dislike tires and wheels that too tightly together, there is a consequence of those that fit too loose:

You must be VERY careful when installing your tube, and check for pinch flats before inflating. The tire bead was so loose with the rim that the tube could move very freely. I found it best to inflate the tube with just a few pounds of pressure, and go around the wheel two or three times to manipulate the tube and put it inside the tire casing, rather than under the tire beads. You must check your work thoroughly to avoid pinch flats and blowouts.

The 700x25mm tires measured right at 26.0mm (at 100 psi) – just slightly narrower than the 26.3mm rim:

Once I got to riding the wheels, I quite liked them. After being overwhelmed by so much tech information, I had no idea whether I was going to love or hate the wheels. In short, they rode as they should – like nice carbon race wheels. They felt sufficiently stiff, the valve extenders worked well, and everything hummed along nicely.

Of particular interest to me was the handling in crosswinds. I’ve ridden a ton of wheels, including many generations of narrow and wide competitors’ products. I took the Reynolds AERO wheels out on a very windy ride in Colorado that included extended climbing and descending. To be honest, I expected the wheels to be twitchy and unstable, but they were anything but that. I was able to stay in my aerobars down all of the same descents that I can on other wheels of similar depth. Despite the various marketing campaigns championing new ways to improve wheel stability, I still find that the real common denominator is good ol’ rim depth and wheel diameter. I don’t care what you do to the shape – a 90mm rim is never going to handle like a 50mm rim.

Braking

Reynolds has been the subject of some criticism in the past about their braking surfaces and problems with heat-related damage and/or rim failure. The AERO line has a new braking surface, which they call CTG. According to Aguero, it has a layer of fiberglass in it that helps to dissipate heat downward into the rim, away from the braking surface.

Note that Reynolds only allows the use of their Cryo blue brake pad with their rim – use of any other pad automatically voids the warranty.

I noticed that, despite various pad setups, my rear brake pads were causing vibration and a very loud howling sound under moderate-to-heavy braking. I tried toeing the pads in, setting them flat, and cleaning all surfaces with 91% isopropyl alcohol – no luck. I also decided to try Zipp’s Tangente Platinum Pro brake pad, which resulted in reduced noise at light-to-moderate braking, but had a similar noise under heavy braking. The stopping distance with both pads was in-line with other carbon clinchers, but the noise was certainly not.

Lew and Aguero suspected that I received a bad batch of pads and mailed a new set out to me.

I also noticed that the rear wheel had come out of true, and about 1mm out of dish after a couple rides. It wasn’t a great deal out of true, but was certainly noticeable to the eye. I also wondered if this contributed to the brake howl and vibration. Unfortunately, I only own a 5.5mm hex driver for deep rims, not the 5.0mm required for these wheels. Reynolds arranged for me to send the rear wheel back to them for inspection and repair, and I had it back in my hands in about two weeks. Since that time, the wheel has stayed perfectly in true and the braking has been quiet.

Even as editors, we have to deal with product problems and warranties. We do not expect perfection – only that problems are dealt with professionally and quickly. In fact, it often gives us a good window in to the warranty process that otherwise might not be possible. Reynolds fixed the wheel in a timely fashion, but it unfortunately arrived at my door without rim tape. I was able to get rolling with some spare 18mm white Zipp rim tape that I had in my parts bin, but the lack of attention-to-detail was mildly disappointing.

Conclusion

Reynolds has a lot of unique features in the AERO line-up. Just recently, they launched a 46mm-deep option to complement the existing 58, 72, and 90mm rims.

After we diagnosed my brake noise and wheel-truing problems, I really enjoyed the wheels. The wide rims are a clear improvement over past Reynolds product. The biggest question mark in my mind is the stability and crosswind story. If I can find the right place and time, I plan to do some back-to-back testing of the Reynolds front wheel with some of my other options. Who has the rim shape ‘right’ in this regard? Do the sharp-edge rims such as the Reynolds AERO and Shimano C50 win – or is it the blunt-shape choices from Profile-Design, Zipp, Hed, and Enve? Does one design do better with a certain amount of wind, or wind direction? Indeed, there are a lot of conflicting marketing messages flying around our industry. I’m not one to believe any of them without some critical thinking and real-world testing, so it looks like we have some work ahead of us.

Start the discussion at forum.slowtwitch.com